Diferencia entre revisiones de «Rumania durante la Primera Guerra Mundial»

Sin resumen de edición |

Revertidos los cambios de 201.223.14.197 a la última edición de 201.223.14.197 usando monobook-suite |

||

| Línea 1: | Línea 1: | ||

{{destruir|esta todo en inglés}} |

|||

{{Traducción inconclusa|art=Romanian Campaign (World War I)|ci=en}} |

{{Traducción inconclusa|art=Romanian Campaign (World War I)|ci=en}} |

||

Revisión del 23:31 8 mar 2010

Plantilla:Warbox Plantilla:FixBunching Plantilla:Campaignbox Romanian Campaign Plantilla:FixBunching Plantilla:WWITheatre Plantilla:FixBunching The Romanian Campaign was a campaign in the Balkan theatre of World War I, with Romania and Russia allied against the armies of the Central Powers.

Antes de la guerra

El Reino de Rumania fue gobernada por reyes de la Casa de Hohenzollern de 1866. El Rey de Rumania, Carol I de Hohenzollern, había firmado un tratado secreto con la Triple Alianza en 1883 que estipulaba que Rumanía se verían obligados a ir a la guerra sólo en el caso de que el Imperio Austro-Húngaro fuese atacado. Mientras que Carol quería entrar en la Primera Guerra Mundial como un aliado de las potencias centrales, la población rumana y los partidos políticos se mostraron a favor de unirse a la Triple Entente. Rumania se mantuvo neutral cuando comenzó la guerra, argumentando que Austria-Hungría se había iniciado la guerra y, en consecuencia, Rumania no tenía ninguna obligación formal para unirse a ella.

Para entrar en la guerra al lado de los aliados, el Reino de Rumania exigía el reconocimiento de sus derechos sobre el territorio de Transilvania, que había sido controlada por Austria-Hungría desde el siglo 17, a pesar de que los rumanos son la mayoría en Transilvania (véase Historia de Transilvania). Los aliados aceptaron los términos finales del verano de 1916(see Tratado de Bucarest, 1916); si Rumania había tomado partido por los Aliados a principios de año, antes de la Ofensiva Brusilov, tal vez el Imperio Ruso, que desconfiaba de Rumanía de su ocupación de Besarabia no habría perdido.[1] Según algunos historiadores militares de América, Rusia retrasó la aprobación de las demandas de Rumania de las preocupaciones sobre los diseños territoriales rumanos sobre Besarabia, que también fue habitada por una mayoría rumana.[2] According to British military historian John Keegan, antes de que Rumanía entró en la guerra los aliados habían acordado en secreto, no honrar a la expansión territorial de Rumania, cuando la guerra terminó.[3]

En 1915, el teniente coronel Christopher Thompson, un orador francés con fluidez, fue enviado a Bucarest como agregado militar británico on Kitchener's initiative to bring Romania into the war. Pero cuando hay que rápidamente formó la opinión de que Rumanía armados preparados y mal frente a una guerra en dos frentes contra Austria-Hungría y Bulgaria sería una responsabilidad no una ventaja para los Aliados. Esta opinión fue desechada por el Whitehall, y firmó un convenio militar con Rumania el 13 de agosto de 1916. A finales de 1916 había para mitigar las consecuencias de los reveses de Rumania, y supervisó la destrucción de los pozos de petróleo de Rumania a negar a Alemania(later Thompson was a Labour peer and Secretary of State for Air).[4]

Plantilla:Historia de Rumania El Gobierno rumano firmó un tratado con los aliados el 17 de agosto de 1916 y declaró la guerra a las Potencias Centrales el 27 de agosto. El Ejército Rumano era bastante grande, más de 500.000 hombres en 23divisiones. However, it had officers with poor training and equipment; more than half of the army was barely trained. Meanwhile, the German Chief of Staff, General Erich von Falkenhayn correctly reasoned that Romania would side with the Allies and made plans to deal with Romania. Thanks to the earlier conquest of the Kingdom of Serbia and the ineffective Allied operations on the Kingdom of Greece border, and having a territorial interest in Dobrogea, the Bulgarian Army and the Ottoman Army were willing to help fight the Romanians.

El alto mando alemán se vio seriamente preocupado por la posibilidad de que Rumania entrara en la guerra, la escritura Hindenburg:

Es cierto que de manera relativamente un pequeño estado como Rumania antes se había dado un papel tan importante, y, de hecho, tan decisivo para la historia del mundo en un momento tan favorable. Nunca antes había dos grandes potencias como Alemania y Austria, se encontraron tan a merced de los recursos militares de un país que apenas una vigésima parte de la población de los dos grandes estados. A juzgar por la situación militar, era de esperar que Rumania no tenía más que antes cuando quería decidir la guerra mundial en favor de las potencias que habían estado lanzando a nosotros mismos en vano durante años. Así, todo parece depender de que Rumania está dispuesta a hacer cualquier tipo de uso de su ventaja momentánea.[5]

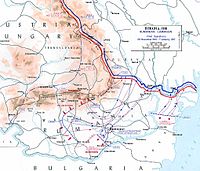

Kingdom of Romania enters the war, late August 1916

On the night of August 27, three Romanian armies (First, Second and Northern), deployed according to the Romanian Campaign Plan (The "Z" Hypothesis), launched attacks through the Carpathians and into Transylvania. The attacks were initially successful in pushing weak units of the Austro-Hungarian First Army out of the mountains. In a relatively short time, the towns of Braşov, Făgăraş and Miercurea Ciuc were freed and the outskirts of Sibiu were reached. Everywhere, the liberating Romanian troops were warmly welcomed by the population, which provided them considerable assistance in terms of provisions, billeting or guiding. But the Austro-Hungarians sent four divisions to reinforce their lines, and by the middle of September, the Romanian offensive was halted. The Russians loaned them three divisions for operations in the north of Romania, but otherwise very few supplies.

While the Romanian army was impetuosly advancing in Transylvania, the first counterattack came from General August von Mackensen in command of a multi-national army of Bulgarian divisions, a German brigade and the Ottoman VI Army Corps consisting of two divisions, whose units began arriving on the Dobrudja front after the initial battles.[6] This army attacked north from Bulgaria, starting on September 1. It stayed on the south side of the Danube river and headed towards Constanţa. The Romanian garrison of Turtucaia, encircled by Bulgarian troops (aided by a column of German troops) surrendered on September 6 (see: Battle of Turtucaia). The Romanian Third Army made further attempts to withstand the enemy offensive at Silistra, Bazargic, Amzacea and Topraisar, but had to withdraw under the pressure of superior enemy forces. Mackensen's success was favoured by the Allies' failure to fulfil the obligation they had assumed through the military convention, by virtue of which they had to mount an offensive on the Macedonian front, and the conditions in which the Russians deployed insufficient troops on the battlefront in the south-east of Romania.

El 15 de septiembre, el Consejo de Guerra de Rumania decidió suspender la ofensiva de Transilvania y destruir el grupo de ejércitos Mackensen lugar. El ejército rumano tuvo que luchar a 1.600 km frente de batalla larga, uno de los más frentes en Europa, con una configuración variados y diversos elementos geográficos, una situación que ningún otro ejército aliado se enfrenta a[cita requerida]. The plan (the so-called Flămânda Maneuver) was to attack the Central Powers forces from the rear by crossing the Danube at Flămânda, while the front-line Romanian and Russian forces were supposed to launch an offensive southwards towards Cobadin and Kurtbunar. On October 1, two Romanian divisions crossed the Danube at Flămânda and created a bridgehead 14 kilometer-wide and 4 kilometer-deep. On the same day, the joint Romanian and Russian divisions went on offensive on the Dobruja front, however with little success. The failure to break the Dobruja front, combined with a heavy storm on the night of October 1/2 which caused heavy damages to the pontoon bridge, determined general Alexandru Averescu to cancel the whole operation. This would have serious consequences for the rest of the campaign.

Russian reinforcements under General Andrei Zaionchkovsky arrived to halt Mackensen's army before it cut the rail line that linked Constanţa with Bucharest. Fighting was furious with attacks and counterattacks up till September 23.

The counteroffensive of the Central Powers (September-December 1916)

Overall command was now under Falkenhayn (recently fired as German Chief of Staff) who started his own counterattack on September 18. The first attack was on the Romanian First Army near the town of Haţeg; the attack halted the Romanian army advance. Eight days later, two German divisions of mountain troops nearly cut off an advancing Romanian column near Nagyszeben (modern day Sibiu). Defeated, the Romanians retreated back into the mountains and the German troops captured Turnu Roşu Pass. El 4 de octubre, el Segundo Ejército rumano atacó la monarquía austro-húngara en Brassó (la actual Braşov), pero el ataque fue repelido y el contraataque de los rumanos obligados a retirarse aquí también. El cuarto ejército rumano, en el norte del país, se retiró sin mucha presión de las tropas austro-húngaro a fin de que el 25 de octubre, el ejército rumano estaba de regreso a sus fronteras en todas partes.

De vuelta a la costa, el general Mackensen lanzó una nueva ofensiva el 20 de octubre, después de un mes de preparativos minuciosos, y su ejército derrotaron a las tropas ruso-rumanas bajo el mando de Zaionchkovsky. The Romanians and Russians were forced to withdraw out of Constanţa (occupied by the Central Powers on October 22). After the fall of Cernavodă, the defense of the unoccupied Dobruja was left only to the Russians, who were gradually pushed back towards the marshy Danube Delta. The Russian army was now both demoralized and nearly out of supplies. Mackensen felt free to secretly pull half his army back to the town of Svishtov (in Bulgaria) with an eye towards crossing the Danube river.

Falkenhayn's forces made several probing attacks into the mountain passes held by the Romanian army to see if there were weaknesses in the Romanian defences. After several weeks, he concentrated his best troops (the elite Alpen Korps) in the south for an attack on the Vulcan Pass. The attack was launched on November 10. One of the young officers was the future Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. On November 11, then-Lieutenant Rommel led the Württemberg Mountain Company in the capture of Mount Lescului. The offensive pushed the Romanian defenders back through the mountains and into the plains by November 26. Ya había nieve de las montañas y las operaciones de pronto tendría que detener para el invierno. Los avances en otras partes del Noveno ejército de Falkenhayn también se abrió paso entre las montañas, el ejército rumano estaba siendo aplastado por la lucha constante y su situación de suministro se está convirtiendo en crítico.

El 23 de noviembre, las mejores tropas de Mackensen cruzaron el Danubio en dos lugares cerca de Svishtov. Este ataque captura por sorpresa a los rumanos y el ejército Mackensen fue capaz de avanzar rápidamente hacia Bucarest contra una resistencia muy débil. Ataque de Mackensen amenazó con cortar la mitad del ejército rumano y por lo que el Comandante Supremo de Rumania (el recientemente ascendido a general Prezan) intentó una desesperada lucha contra-ataque de la fuerza de Mackensen. El plan era audaz, utilizando las reservas de todo el ejército rumano, pero se necesita la cooperación de las divisiones de Rusia para contener la ofensiva de Mackensen, mientras la reserva rumano golpeó la brecha entre Mackensen y Falkenhayn. Sin embargo, el ejército ruso no está de acuerdo con el plan y no apoyó el ataque.

El 1 de diciembre, el ejército rumano siguió adelante con la ofensiva. Mackensen fue capaz de cambiar sus fuerzas para hacer frente al asalto repentino y las fuerzas de Falkenhayn respondió con ataques en cada punto. Dentro de tres días, el ataque había sido destrozado y los rumanos se retiraban por todas partes. El Gobierno rumano y el Real Tribunal de Justicia se trasladaron a Iaşi. Bucharest was captured el 6 de diciembre por la caballería de Falkenhayn's. Las lluvias y las carreteras terribles fueron las únicas cosas que guarda el resto del ejército rumano, más de 150.000 soldados rumanos fueron capturados.

Los rusos se vieron obligados a enviar muchas divisiones a la zona fronteriza para evitar una invasión del sur de Rusia. El Ejército Austro-Húngaro, después de varios combates, se libró a un punto muerto a mediados de enero de 1917. El ejército rumano todavía luchado, pero la mitad de Rumania estaba bajo ocupación alemana.

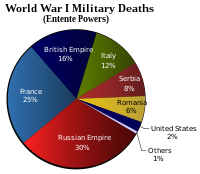

Las bajas rumanas se estiman en alrededor de 250.000 (incluidos los prisioneros de guerra)[cita requerida]. Las pérdidas alemanas,austriacas,búlgaras, y otomanas se estiman en 60,000.[cita requerida]

La contraofensiva de 1916 fue una hazaña impresionante para el ejército alemán y sus generales Falkenhayn y Mackensen[7] así como el ejército búlgaro[cita requerida] comandado por Stefan Toshev,Panteley Kiselov y Todor Kantardzhiev.

The 1917 campaign

La lucha continuó en 1917, como la parte norte de Rumania, porque se mantuvo independiente de la estrategia de triángulo, under which the Romanian Fourth Army (escaping destruction due to weather mentioned earlier), remained in the mountains in Moldavia, protecting Iaşi against repeated German offensives. In May 1917, the Romanian Army attacked alongside the Russians in support of the Kerensky Offensive. After succeeding in breaking the Austro-Hungarian front in the Battle of Mărăşti, los rusos y los rumanos tuvieron que detener su avance debido al desastre de la ofensiva de Kerensky. Mackensen lanzó entonces un contraataque sin éxito en Mărăşeşti, y al mismo tiempo, an Austro-Hungarian offensive at Oituz also failed. En conjunto, estas operaciones representa un éxito importante para Rumania, como los territorios desocupados (la mayoría de Moldavia) se mantuvo libre.

Cuando los bolcheviques tomaron el poder en Rusia y han firmado el Tratado de Brest-Litovsk, Rumanía quedó aislada y rodeada por las potencias centrales y que no había más remedio que negociar un armisticio, firmado por los combatientes el 9 de diciembre de 1917, en Focşani.

Aftermath

Treaty of Bucharest

Plantilla:Expand Plantilla:See

On May 7, 1918, Romania was forced[cita requerida] to conclude the Treaty of Bucharest with the Central Powers.

Los alemanes fueron capaces de reparar los campos petroleros alrededor de Ploieşti y por el final de la guerra había bombeado un millón de toneladas de petróleo. También se requisaron dos millones de toneladas de granos de los agricultores rumanos. Estos materiales fueron vitales para mantener a Alemania en la guerra hasta el final de 1918.[8]

Rumanía vuelve a entrar en la guerra, noviembre de 1918

Después de la ofensiva con éxito en Tesalónica que puso frente a Bulgaria fuera de la guerra, Rumania volvió a entrar en la guerra el 10 de noviembre de 1918, un día antes de su final en el Oeste.

El 28 de noviembre de 1918, los representantes rumanos de Bucovina votó a favor de la unión con el Reino de Rumania, seguida de la proclamación de la unión de Transilvania con el Reino de Rumania del 1 diciembre de 1918, por los representantes de los rumanos de Transilvania se reunieron en Alba Iulia,mientras que los representantes de la sajones de Transilvania aprobaron la Ley del 15 de diciembre en una asamblea en Mediaş.

El Tratado de Versalles reconoce estas declaraciones en el marco del derecho de autodeterminación de los pueblos (see the Wilsonian Fourteen Points). También Alemania estuvo de acuerdo en los términos del mismo Tratado (artículo 259) a renunciar a todas las prestaciones previstas por el Tratado de Bucarest en 1918.[9]

El control rumano de Transilvania, que también había una población húngara de 1.662.000 habitantes(34%, according to the census data of 1910), was widely resented in the new nation state of Hungary. A war between the Hungarian Soviet Republic y el Reino de Rumania, que formaba parte de una fuerza de la Entente con los ejércitos de Serbia y Hungría, Checoslovaquia atacando por todos lados, se libró en 1919 y terminó con una ocupación parcial rumana de Hungría. Las fuerzas rumanas más tarde instauraron al almirante Míklos Horthy como regente de Hungría.

Análisis militar de la campaña

Claramente, Rumania entró en la guerra en un mal momento. La entrada en el lado de los aliados en 1914 o 1915 podría haber evitado la conquista de Serbia. Entrada a principios de 1916 podría haber permitido la ofensiva Brusilov para tener éxito. La desconfianza mutua fue compartida por Rumanía y la gran potencia que estaba en la posición de ayudar directamente a él, Rusia.

General Vincent Esposito sostiene que el alto mando de Rumania hizo graves errores estratégicos y operativos:

Militarmente, la estrategia de Rumanía no podía haber sido peor. En la elección de Transilvania como el objetivo inicial, el ejército rumano ignorado el Ejército de Bulgaria a su trasero. Cuando el avance a través de las montañas no, el alto mando se negó a ahorrar fuerzas en ese frente para permitir la creación de una reserva móvil con el que empuja más tarde Falkenhayn podría ser contrarrestado. En ninguna parte de los rumanos en masa adecuadamente sus fuerzas para alcanzar la concentración de poder combativo.[7]

El fracaso del frente de Rumanía para la Entente fue también el resultado de varios factores fuera del control de ésta. The failed Salonika Offensive did not meet the expectation of Romania's "guaranteed security" from Bulgaria.[10] This proved to be a critical strain on Romania's ability to wage a successful offensive in Transylvania, as it needed to divert troops south to the defense of Dobruja.[11] Furthermore, Russian reinforcements in Romania did not materialize to the number of 200,000 soldiers initially demanded.[12] Rumania se convirtió así en una situación difícil, varios meses después se unió a la guerra, con la Entente en condiciones de proporcionar el apoyo que había prometido a principios.

References

- ↑ Cyril Falls, The Great War p. 228

- ↑ Vincent Esposito, Atlas of American Wars, Vol 2, text for map 37

- ↑ John Keegan, The First World War, pg. 306

- ↑ To Ride the Storm: The Story of the Airship R.101 by Sir Peter G. Masefield, pages 16-17 (1982, William Kimber, London) ISBN 0 7183 0068 8

- ↑ Paul von Hindenburg, Out of My Life, Vol. I, trans. F.A. Holt (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1927), 243.

- ↑ Българската армия в Световната война 1915 - 1918, vol. VIII , pag. 282-283

- ↑ a b Vincent Esposito, Atlas of American Wars, Vol 2, text for map 40

- ↑ John Keegan, World War I, pg. 308

- ↑ Articles 248 - 263 - World War I Document Archive

- ↑ Torrey, Romania and World War I, p. 27

- ↑ Istoria României, Vol. IV, p. 366

- ↑ Torrey, Romania and World War I, p. 65

Sources

- Esposito, Vincent (ed.) (1959). The West Point Atlas of American Wars - Vol. 2; maps 37-40. Frederick Praeger Press.

- Falls, Cyril. The Great War (1960), ppg 228-230.

- Keegan, John. The First World War (1998), ppg 306-308. Alfred A. Knopf Press.

See also

Portal:World War I. Contenido relacionado con World War I.

Portal:World War I. Contenido relacionado con World War I.

External links

Plantilla:WWI history by nation Plantilla:Romanian topics Plantilla:World War I Plantilla:Bulgaria in World War I