Usuario:Кардам/Taller

Reinaldo de Châtillon (c. 1124 – 4 de julio de 1187), fue príncipe de Antioquía —un Estado cruzado en Oriente Próximo— de 1153 a 1160 o 1161, y señor de Transjordania —un gran feudo en el Reino de Jerusalén— desde 1175 hasta su muerte, gobernando ambos territorios por iure uxoris ('por derecho de esposa'). Siendo el hijo menor de un noble francés, se unió a la segunda cruzada en 1147 y se estableció en Jerusalén como mercenario. Seis años más tarde, se casó con la princesa Constanza de Antioquía, aunque sus súbditos consideraron el matrimonio como una hipergamia.

Siempre necesitado de fondos, Reinaldo torturó a Emerico de Limoges, patriarca latino de Antioquía, que se había negado a pagarle un subsidio y 1156, lanzó una incursión de saqueo en Chipre, que causó una gran destrucción en este territorio perteneciente al Imperio bizantino. Cuatro años más tarde, Manuel I Comneno, el emperador bizantino, dirigió un ejército hacia Antioquía, que lo obligó a aceptar su soberanía. En 1160 o 1161, Reinaldo se encontraba atacando el valle del río Éufrates cuando el gobernador de Alepo lo capturó en Marash y sería liberado mediante un gran rescate en 1176, pero no regresó a Antioquía porque su esposa había muerto mientras tanto. En 1177, se casó con Estefanía de Milly, la rica heredera de Transjordania, y dado que Balduino IV de Jerusalén le concedió también el Señorío de Hebrón, se convirtió en uno de los barones más ricos del reino. Después de que el rey, que padecía lepra, lo nombrara regente ese mismo año, dirigió el ejército cruzado que derrotó a Saladino, sultán Egipto y Siria, en la batalla de Montgisard. Al controlar las rutas de las caravanas entre Egipto y Siria, Reinaldo era el único caudillo cristiano que siguió una política ofensiva contra Saladino, realizando incursiones de saqueo contra las caravanas que viajaban cerca de sus dominios. Después de que su recién construida flota saqueara la costa del mar Rojo a principios de 1183, amenazando la ruta de los peregrinos musulmanes a La Meca, el sultán prometió nunca perdonarlo.

Reinaldo era un firme partidario de la hermana de Balduino IV, Sibila, y de su marido, Guido de Lusignan, durante los conflictos relacionados con la sucesión del rey; la pareja tomar el trono en 1186 gracias a su cooperación y de Joscelino III de Courtenay, tío de la reina. A pesar de una tregua entre cristianos y musulmanes, atacó una caravana que viajaba de Egipto a Siria a finales de 1186 o principios de 1187, alegando que la tregua no lo relacionaba. Después de negarse a pagar una compensación, el sultán invadió el reino y aniquiló al ejército cruzado en la batalla de Hattin, donde fue capturado. Saladino lo decapitó en persona por sus actos de bandidaje y otros crímenes luego de que rechazara convertirse al Islam. La mayoría de los historiadores lo han considerado como un aventurero irresponsable cuya ansia de botín provocó la caída del Reino de Jerusalén. Por otro lado, el historiador Bernard Hamilton dice que fue el único comandante cruzado que intentó impedir la unificación de los estados musulmanes cercanos.

Primeros años[editar]

Reinaldo era el hijo menor de Hervé II, señor de Donzy en el Reino de Francia.[1][2] En la historiografía más antigua, se pensaba que era hijo de Geoffrey, conde de Gien,[3] pero el historiador Jean Richard demostró su parentesco con los señores de Donzy.[nota 1] Eran nobles influyentes en el Ducado de Borgoña (en la actual Francia oriental), que afirmaban descender de los Paladio, una prominente familia aristocrática galorromana.[1][5] La madre de Reinaldo era una hija anónima de Hugo el Blanco, señor de La Ferté-Milon.[6]

Nacido hacia 1124, Reinaldo heredó el Señorío de Châtillon-sur-Loire.[1][7] Años más tarde, se quejaría en una carta a Luis VII de Francia de que una parte de su patrimonio fue «confiscada violenta e injustamente». El historiador Malcolm Barber dice que probablemente este acontecimiento lo impulsó a abandonar su tierra natal hacia los Estados cruzados.[nota 2][9] Según los historiadores modernos, llegó al Reino de Jerusalén en el ejército de Luis VII durante la segunda cruzada en 1147,[nota 3] y se quedó cuando los franceses abandonaron la campaña militar dos años después.[11][9] A principios de 1153, se sabe que combatió en el ejército de Balduino III de Jerusalén durante el asedio de Ascalón.[12]

Guillermo de Tiro, historiador del siglo XII, era un oponente político de Reinaldo y lo describe como «una especie de caballero mercenario», enfatizando su clase social con la princesa Constanza de Antioquía, con quien inesperadamente se comprometió a casarse antes del final del asedio.[12][9] La princesa era la única hija y sucesora de Bohemundo II de Antioquía y había enviudado cuando su consorte, Raimundo de Poitiers cayó en la batalla de Inab el 28 de junio de 1148.[13][14] Para asegurar la defensa de Antioquía, Balduino III, que era primo de Constanza, dirigió su ejército a Antioquía al menos tres veces durante los años siguientes. Intentó persuadir a su prima para que se volviera a casar, pero no aceptó a sus candidatos. También rechazó a Juan Roger, a quien el emperador bizantino Manuel I Comneno había propuesto como cónyuge.[15][16] La pareja mantuvo su compromiso en secreto hasta que el rey concedió su permiso para casarse.[3][9] Según el historiador Andrew D. Buck, necesitaban un permiso real porque Reinaldo estaba al servicio de Balduino III.[17] La crónica de principios del siglo XIII conocida como Estoire d'Eracles afirma que consintió felizmente en el matrimonio porque lo liberaba de su obligación de «defender una tierra» (Antioquía) «que estaba tan lejos» de su reino.[18]

Prince of Antioch[editar]

Después que el rey diera su consentimiento, Constanza se casó con Reinaldo. [3] [9] [19] Fue instalado como príncipe en mayo de 1153 o poco antes. [20] En ese mes, confirmó los privilegios de los comerciantes venecianos. [21] Guillermo de Tiro registra que sus súbditos estaban asombrados de que su princesa "famosa, poderosa y de alta nobleza" se casara con un hombre de bajo estatus. [12] No ha sobrevivido ninguna moneda acuñada para Reinaldo. Según Buck, esto indica que su posición era relativamente débil. Mientras que Raimundo de Poitiers había emitido alrededor de la mitad de sus cartas sin hacer referencia a Constanza, Reinaldo siempre mencionó que tomó la decisión con el consentimiento de su esposa. [22] Reinaldo controló los nombramientos para los cargos más altos: nombró a Geoffrey Jordanis condestable y a Geoffrey Falsard duque de Antioquía. [nota 4] [24]

El cronista normando Roberto de Torigni escribe que Reinaldo se apoderó de tres fortalezas de los alemanes poco después de su ascenso, pero no las nombra. [25] Emerico de Limoges, el rico patriarca latino de Antioquía, no ocultó su consternación ante el segundo matrimonio de Constanza. Incluso se negó a pagar una subvención a Reinaldo, aunque Reinaldo, como subraya Barber, "tenía extrema necesidad de dinero". En represalia por la negativa de Emerico, Reinaldo lo arrestó y torturó en el verano de 1154, obligándolo a sentarse desnudo y cubierto de miel al sol, antes de encarcelarlo. Emerico sólo fue liberado a petición de Balduino III, pero pronto abandonó Antioquía y se dirigió a Jerusalén. [26] [19] [27] Sorprendentemente, Reinaldo no fue excomulgado por su abuso de un clérigo de alto rango. Buck sostiene que Reinaldo podría evitar el castigo debido a las disputas previas de Emerico con el papado sobre el arzobispado de Tiro. En cambio, Emerico excomulgó a Reinaldo a petición del papado en 1154 como consecuencia de un conflicto entre Antioquía y Génova. [28]

El emperador Manuel, que reclamaba soberanía sobre Antioquía, envió sus enviados a Reinaldo, [nota 5] proponiendo reconocerlo como el nuevo príncipe si lanzaba una campaña contra los armenios de Cilicia, que se habían levantado contra el dominio bizantino. [nota 6] También prometió que compensaría a Reinaldo por los gastos de la campaña. [19] Después de que Reinaldo derrotara a los armenios en Alejandreta en 1155, los caballeros templarios tomaron el control de la región de las Puertas Sirias que los armenios habían invadido recientemente. [32] Aunque las fuentes no están claras, Runciman y Barber coinciden en que fue Reinaldo quien les concedió el territorio. [32] [27]

Siempre necesitado de fondos, Reinaldo instó a Manuel a que le enviara el subsidio prometido, pero Manuel no pagó el dinero. [27] Reinaldo hizo una alianza con el señor armenio Teodoro II de Cilicia. Atacaron Chipre y saquearon la próspera isla bizantina durante tres semanas a principios de 1156. [33] [34] Al escuchar rumores de que una flota imperial se acercaba a la isla, abandonaron Chipre, pero sólo después de haber obligado a todos los chipriotas a pagar un rescate, con el excepción de los individuos más ricos (incluido el sobrino de Manuel, Juan Ducas Comneno), a quienes se llevaron a Antioquía como rehenes. [33] [35]

Aprovechando la presencia de Teodorico, conde de Flandes, y su ejército en Tierra Santa y un terremoto que había destruido la mayoría de las ciudades del norte de Siria, Balduino III de Jerusalén invadió los territorios musulmanes en el valle del río Orontes en el otoño de 1157. [36] Reinaldo se unió al ejército real y sitiaron Shaizar. [35] [36] En este punto, Shaizar estaba en manos de los asesinos chiítas, pero antes del terremoto había sido la sede de los munqidhitas sunitas que pagaban un tributo anual a Reinaldo. [36] Balduino planeaba conceder la fortaleza a Thierry de Flandes, pero Reinaldo exigió que el conde le rindiera homenaje por la ciudad. Después de que Thierry se negara rotundamente a jurar lealtad a un advenedizo, los cruzados abandonaron el asedio. [37] Marcharon sobre Harenc (actual Harem, Siria), que había sido una fortaleza antioquena antes de que Nur al-Din la capturara en 1150. [38] Después de que los cruzados capturaran Harenc en febrero de 1158, Reinaldo se lo concedió a Reinaldo de Saint-Valery de Flandes. [37] [39]

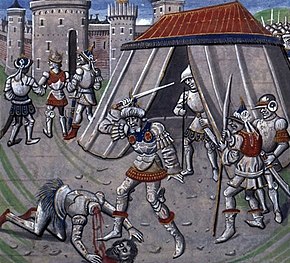

El emperador Manuel invadió inesperadamente Cilicia, lo que obligó a Teodoro II a buscar refugio en las montañas en diciembre de 1158. [40] [41] Incapaz de resistir una invasión bizantina a gran escala, Reinaldo se apresuró a ir a Mamistra para someterse voluntariamente al emperador. [40] [39] A petición de Manuel, Reinaldo y sus sirvientes caminaron descalzos y con la cabeza descubierta por las calles de la ciudad hasta la tienda imperial donde se postró, suplicando clemencia. [42] Guillermo de Tiro afirmó que "la gloria del mundo latino quedó avergonzada" en esta ocasión, porque los enviados de los gobernantes musulmanes y cristianos cercanos también estuvieron presentes en la humillación de Reinaldo. [43] Manuel exigió que se instalara un patriarca griego en Antioquía. Aunque su demanda no fue aceptada, la evidencia documental indica que Gerard, el obispo católico de Latakia, se vio obligado a trasladarse a Jerusalén. [44] Reinaldo tuvo que prometer que permitiría que una guarnición bizantina permaneciera en la ciudadela cuando fuera necesario y que enviaría una tropa a luchar en el ejército bizantino. [42] En poco tiempo, Balduino III de Jerusalén persuadió a Manuel para que aceptara el regreso del patriarca latino, Emerico, a Antioquía, en lugar de instalar un patriarca griego. Cuando el emperador entró en Antioquía con mucha pompa y ceremonia el 12 de abril de 1159, Reinaldo sujetaba las riendas del caballo de Manuel. [41] [45] Manuel abandonó el pueblo ocho días después. [46]

Reinaldo realizó una incursión de saqueo en el valle del río Éufrates en Marash para apoderarse de ganado, caballos y camellos de los campesinos locales en noviembre de 1160 o 1161. [47] [48] [49] Majd al-Din, comandante de Nur al-Din de Alepo, reunió sus tropas (10.000 personas, según el historiador contemporáneo Mateo de Edesa), y atacó a Reinaldo y su séquito en el camino de regreso a Antioquía. [47] [50] Reinaldo intentó luchar, pero lo desmontaron y lo capturaron. Lo enviaron a Alepo, donde lo encarcelaron. [48]

Captivity and release[editar]

Almost nothing is known about Raynald's life while he was imprisoned for fifteen years.[19] He shared his prison with Joscelin III of Courtenay, the titular Count of Edessa, who had been captured a couple of months before him.[20] In Raynald's absence, Constance wanted to rule alone, but Baldwin III of Jerusalem made Patriarch Aimery regent for her fifteen-year-old son (Raynald's stepson), Bohemond III of Antioch.[20][21] Constance died around 1163, shortly after her son reached the age of majority.[22] Her death deprived Raynald of his claim to Antioch.[19] However, he had become an important personality, with prominent family connections, as his stepdaughter, Maria of Antioch, married Emperor Manuel in 1161, and his own daughter, Agnes, became the wife of Béla III of Hungary.[19]

Nur ad-Din died unexpectedly in 1174. His underage son as-Salih Ismail al-Malik succeeded him, and Nur ad-Din's mamluk ('slave-soldier') Gümüshtekin assumed the regency for him in Aleppo. Being unable to resist attacks by the ambitious Kurdish warlord Saladin, Gümüshtekin sought the support of Raynald's stepson Bohemond III of Antioch, and on his request released Raynald along with Joscelin of Courtenay and all other Christian prisoners in 1176.[23][24] Raynald's ransom, fixed at 120,000 gold dinars, reflected his prestige.[19] It was most probably paid by Emperor Manuel, according to Barber and Hamilton.[25][26]

Raynald came to Jerusalem with Joscelin before 1 September 1176,[27] where he became a close ally of Joscelin's sister, Agnes of Courtenay.[28] She was the mother of the young Baldwin IV of Jerusalem, who suffered from leprosy.[28][29] Hugo Etherianis, who lived in Constantinople after about 1165, mentioned in the preface of his work About the Procession of the Holy Spirit, that he had asked "Prince Raynald" to deliver a copy of the work to Aimery of Limoges.[30] Hamilton writes that these words suggest that Raynald led the embassy that Baldwin IV sent to Constantinople to confirm an alliance between Jerusalem and the Byzantine Empire against Egypt towards the end of 1176.[30][31]

Lord of Oultrejordain[editar]

First years[editar]

After his return from Constantinople early in 1177, Raynald married Stephanie of Milly, the lady of Oultrejordain, and Baldwin IV also granted him Hebron.[32] The first extant charter styling Raynald as "Lord of Hebron and Montréal" was issued in November 1177.[33] He owed service of 60 knights to the Crown, showing that he had become one of the wealthiest barons of the realm.[32][34] From his castles at Kerak and Montréal, he controlled the routes between the two main parts of Saladin's empire, Syria and Egypt.[35] Raynald and Baldwin IV's brother-in-law, William of Montferrat, jointly granted large estates to Rodrigo Álvarez, the founder of the Order of Mountjoy, to strengthen the defence of the southern and eastern frontier of the kingdom.[32] After William of Montferrat died in June 1177, the king made Raynald regent of the kingdom.[36]

Baldwin IV's cousin, Philip I, Count of Flanders, came to the Holy Land at the head of a crusader army in early August 1177.[35] The king offered him the regency, but Philip refused the offer, saying that he did not want to stay in the kingdom.[37] Philip declared that he was "willing to take orders" from anybody, but he protested when Baldwin confirmed Raynald's position as "regent of the kingdom and of the armies" as he thought that a military commander without special powers should lead the army.[38] Philip left the kingdom a month after his arrival.[39]

Saladin invaded the region of Ascalon, but the royal army launched an attack on him in the Battle of Montgisard on 25 November, leading to his defeat.[40] William of Tyre and Ernoul attributed the victory to the king, but Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad and other Muslim authors recorded that Raynald was the supreme commander.[41] Saladin himself referred to the battle as a "major defeat which God mended with the famous battle of Hattin",[42] according to Baha ad-Din.[43]

Raynald signed a majority of royal charters between 1177 and 1180, with his name always first among signatories, showing that he was the king's most influential official during this period.[44] Raynald became one of the principal supporters of Guy of Lusignan, who married the king's elder sister, Sybilla, in early 1180, although many barons of the realm had opposed the marriage.[45][46] The king's half sister, Isabella (whose stepfather, Balian of Ibelin, was Guy of Lusignan's opponent), was engaged to Raynald's stepson, Humphrey IV of Toron, in autumn 1180.[45]

Baldwin IV dispatched Raynald, along with Heraclius, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, to mediate a reconciliation between Bohemond III of Antioch and Patriarch Aimery in early 1181.[47][48] The same year, Roupen III, Lord of Cilician Armenia, married Raynald's stepdaughter, Isabella of Toron.[49]

Fights against Saladin[editar]

Raynald was the only Christian leader who fought against Saladin in the 1180s.[50][51] The contemporary chronicler Ernoul mentions two raids that Raynald made against caravans travelling between Egypt and Syria, breaking the truce.[52] Modern historians debate whether Raynald's military actions sprang from a desire for booty,[53] or were deliberate maneuvers to prevent Saladin from annexing new territories.[51] After as-Salih died on 18 November 1181, Saladin tried to seize Aleppo, but Raynald stormed into Saladin's territory, reaching as far as Tabuk on the route between Damascus and Mecca.[54] Saladin's nephew, Farrukh Shah, invaded Oultrejordain instead of attacking Aleppo to compel Raynald to return from the Arabian Desert.[55] Before long, Raynald seized a caravan and imprisoned its members.[55] On Saladin's protest, Baldwin IV ordered Raynald to free them, but Raynald refused.[56] His defiance annoyed the king, enabling Raymond III of Tripoli's partisans to reconcile him with the monarch.[57] A close relative of Baldwin, Raymond had assumed the regency in 1174 but was banned from the kingdom for allegedly plotting against the ailing king.[58] Raymond's return to the royal court put an end to Raynald's paramount position. After accepting the new situation, Raynald cooperated with the king and Raymond during the fights against Saladin in the summer of 1182.[59]

Saladin revived the Egyptian naval force and tried to capture Beirut, but his ships were forced to retreat.[60] Raynald ordered the building of at least five ships in Oultrejordain. They were carried across the Negev desert to the Gulf of Aqaba at the northern end of the Red Sea in January or February 1183.[61][62][63] He captured the fort of Ayla (present-day Eilat in Israel), and attacked the Egyptian fortress on Pharaoh's Island. Part of his fleet made a plundering raid along the coasts against ships delivering Muslim pilgrims and goods, threatening the security of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.[61][64] Raynald left the island, but his fleet continued the siege.[65] Saladin's brother, al-Adil, the governor of Egypt, dispatched a fleet to the Red Sea. The Egyptians relieved Pharaoh's Island and destroyed the Christian fleet. Some of the soldiers were captured near Medina because they landed either to escape or to attack the city. Raynald's men were executed, and Saladin took an oath that he would never forgive him.[65][66] Though Raynald's naval expedition "showed a remarkable degree of initiative" according to Hamilton, most modern historians agree that it contributed to the unification of Syria and Egypt under Saladin's rule.[67] Saladin captured Aleppo in June 1183, completing the encirclement of the crusader states.[68]

Baldwin IV, who had become seriously ill, made Guy of Lusignan regent in October 1183.[69] Within a month, Baldwin had dismissed Guy, and had Guy's five-year-old stepson, Baldwin V, crowned king in association with himself.[70] Raynald was not present at the child's coronation, because he was at the wedding of his stepson, Humphrey, and Baldwin IV's sister, Isabella, in Kerak.[71] Saladin unexpectedly invaded Oultrejordain, forcing the local inhabitants to seek refuge in Kerak.[71] After Saladin broke into the town, Raynald only managed to escape to the fortress because one of his retainers had hindered the attackers from seizing the bridge between the town and the castle.[72] Saladin laid siege to Kerak.[73] According to Ernoul, Raynald's wife sent dishes from the wedding to Saladin, persuading him to stop bombarding the tower where her son and his wife stayed.[73] After envoys from Kerak informed Baldwin IV of the siege, the royal army left Jerusalem for Kerak under the command of the king and Raymond III of Tripoli.[73] Saladin abandoned the siege before their arrival on 4 December.[73] On Saladin's order, Izz ad-Din Usama had a fortress built at Ajloun, near the northern border of Raynald's domains.[74]

Kingmaker[editar]

Baldwin IV died in early 1185.[61] His successor, the child Baldwin V, died in late summer 1186.[75] The High Court of Jerusalem had ruled that neither Baldwin V's mother, Sybilla (who was Guy of Lusignan's wife), nor her sister, Isabella (who was the wife of Raynald's stepson), could be crowned without the decision of the pope, the Holy Roman Emperor, and the kings of France and England on Baldwin V's lawful successor.[76] However, Sybilla's uncle, Joscelin III of Courtenay, took control of Jerusalem with the support of Raynald and other influential prelates and royal officials.[77][78] Raynald urged the townspeople to accept Sybilla as the lawful monarch, according to the Estoire d'Eracles.[79] Raymond III of Tripoli, and his supporters tried to prevent her coronation and reminded her partisans of the decision of the High Court.[80] Ignoring their protest, Raynald and Gerard of Ridefort, Grand Master of the Knights Templar, accompanied Sybilla to the Holy Sepulchre, where she was crowned.[80] She also arranged the coronation of her husband, although he was unpopular even among her supporters.[81][82] Her opponents tried to persuade Raynald's stepson, Humphrey, to claim the crown on his wife's behalf, but Humphrey deserted them and swore fealty to Sybilla and Guy.[83][82] Raynald headed the list of secular witnesses in four royal charters issued between 21 October 1186 and 7 March 1187, showing that he had become a principal figure in the new king's court.[84]

Ali ibn al-Athir and other Muslim historians stated that Raynald made a separate truce with Saladin in 1186.[74] This "seems unlikely to be true", according to Hamilton, because the truce between the Kingdom of Jerusalem and Saladin legally covered Raynald's domains as they formed a large fiefdom in the kingdom.[74] In late 1186 or early 1187, a rich caravan travelled through Oultrejordain from Egypt to Syria.[74] Ali ibn al-Athir mentioned that a group of armed men accompanied the caravan.[85] Raynald seized the caravan, possibly because he regarded the presence of soldiers as a breach of the truce, according to Hamilton.[86][87] He took all the merchants and their families prisoner, seized a large amount of booty, and refused to receive envoys from Saladin demanding compensation.[87][88] Saladin sent his envoys to Guy of Lusignan, who accepted his demands.[87] However, Raynald refused to obey the king, stating in the words of the Estoire d'Eracles that "he was lord of his land, just as Guy was lord of his, and he had no truces with the Saracens". For Barber, Raynald's disobedience indicates that the kingdom was "on the brink of breaking up into a collection of semi-autonomous fiefdoms" under Guy's rule.[87] Saladin proclaimed a jihad (or holy war) against the kingdom, taking an oath that he would personally kill Raynald for breaking the truce.[89] The historian Paul M. Cobb remarks that Saladin "badly needed a victory against the Franks to silence those who criticized him for spending so much time at war with his fellow Muslims".[90]

Prince Reynald, lord of Kerak, was one of the greatest and wickedest of the Franks, the most hostile to the Muslims and the most dangerous to them. Aware of this, Saladin targeted him with blockades time after time and raided his territory occasion after occasion. As a result he was abashed and humbled and asked Saladin for a truce, which was granted. The truce was made and duly sworn to. Caravans then went back and forth between Syria and Egypt. [In the year 582 AH], a large caravan, rich in goods and with many men, accompanied by a good number of soldiers, passed by him. The accursed one treacheously seized every last man and made their goods, animals and weapons his booty. Those he made captive he consigned to his prisons. Saladin sent blaming him, deploring his treacherous action and threatening him if he did not release the captives and the goods, but he would not agree to do that and persisted in his refusal. Saladin vowed that, if ever had him in his power, he would kill him.

|

Capture and execution[editar]

The Estoire d'Eracles incorrectly claims that Saladin's sister was also among the prisoners taken by Raynald when he seized the caravan.[74][88] She returned from Mecca to Damascus in a separate pilgrim caravan in March 1187.[74] To protect her against an attack by Raynald, Saladin escorted the pilgrims while they were travelling near Oultrejordain.[92] Saladin stormed into Oultrejordain on 26 April and pillaged Raynald's domains for a month.[93] Thereafter, Saladin marched to Ashtara on the road between Damascus and Tiberias, where the troops coming from all parts of his realm assembled.[94][95]

The Christian forces assembled at Sepphoris.[94][96] Raynald and Gerard of Ridefort persuaded Guy of Lusignan to take the initiative and attack Saladin's army, although Raymond III of Tripoli had tried to persuade the king to avoid a direct fight with it.[85][97] During the debate, Raynald accused Raymond of Tripoli of co-operating with the enemy.[98] Raynald and Rideford had fatally misjudged the situation.[85] Saladin inflicted a crushing defeat on the crusaders in the Battle of Hattin on 4 July, and most commanders of the Christian army were captured on the battlefield.[99]

Guy of Lusignan and Raynald were among the prisoners who were brought before Saladin.[100] Saladin handed a cup of iced rose water to Guy.[101] After drinking from the cup, the king handed it to Raynald.[101] Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani (who was present) recorded that Raynald drank from the cup.[100] Since customary law prescribed that a man who gave food or drink to a prisoner could not kill him, Saladin pointed out that it was Guy who had given the cup to Raynald.[101] After calling Raynald to his tent,[100] Saladin accused him of many crimes (including brigandage and blasphemy), offering him to choose between conversion to Islam or death, according to Imad ad-Din and Ibn al-Athir.[85][101] After Raynald flatly refused to convert, Saladin took a sword and struck Raynald with it.[85][101] As Raynald fell to the ground, Saladin beheaded him.[85][102] The reliability of the reports of Saladin's offer to Raynald is subject to scholarly debate, because the Muslim authors who recorded them may have only wanted to improve Saladin's image.[103] Ernoul's chronicle and the Estoire d'Eracles recount the events ending with Raynald's execution in almost the same language as the Muslim authors.[101] However, according to Ernoul's chronicle, Raynald refused to drink from the cup that Guy of Lusignan handed to him.[100][104] According to Ernoul, Raynald's head was struck off by Saladin's soldiers and it was brought to Damascus to be "dragged along the ground to show the Saracens, whom the prince had wronged, that vengeance had been exacted".[105][104] Baha ad-Din also wrote that Raynald's fate shocked Guy of Lusignan, but Saladin soon comforted him, stating that "A king does not kill a king, but that man's perfidy and insolence went too far".[106]

Family[editar]

Raynald's first wife, Constance of Antioch (born in 1128), was the only daughter of Bohemond II of Antioch and Alice of Jerusalem.[107] Constance succeeded her father in Antioch in 1130.[108] Six years later, she was given in marriage to Raymond of Poitiers who died in 1149.[109] The widowed Constance's marriage to Raynald is described as "the misalliance of the century" by Hamilton,[11] but Buck emphasises that "the marriage went unmentioned in Western chronicles".[17] Buck adds that Raynald's relatively low birth "actually made him the ideal candidate" to marry the widowed princess who had a son with a strong claim to rule upon reaching the age of majority, and Raynald was possibly "expected to eventually step aside".[110]

The daughter of Raynald and Constance, Agnes, moved to Constantinople in early 1170 to marry Alexios-Béla, the younger brother of Stephen III of Hungary, who lived in the Byzantine Empire.[111] Agnes was renamed Anna in Constantinople.[112] Her husband succeeded his brother as Béla III of Hungary in 1172.[113] She followed her husband to Hungary, where she gave birth to seven children before she died around 1184.[112] Raynald and Constance's second daughter, Alice, became the third wife of Azzo VI of Este in 1204.[114] Raynald also had a son, Baldwin, from Constance, according to Hamilton and Buck, but Runciman says that Baldwin was Constance's son from her first husband.[115][116][117] Baldwin moved to Constantinople in the early 1160s.[22] He died fighting at the head of a Byzantine cavalry regiment in the Battle of Myriokephalon on 17 September 1176.[118]

Raynald's second wife, Stephanie of Milly, was the younger[119] daughter of Philip of Milly, Lord of Nablus, and Isabella of Oultrejordain.[120] She was born around 1145.[121] Her first husband, Humphrey III of Toron, died around 1173.[122] She inherited Oultrejordain from her niece, Beatrice Brisbarre, shortly before she married Miles of Plancy in early 1174.[122] Miles of Plancy was murdered in October 1174.[123][119]

Historiography and perceptions[editar]

Most information on Raynald's life was recorded by Muslim authors, who were hostile to him.[124] Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad described him as a "monstrous infidel and terrible oppressor"[125] in his biography of Saladin.[126] Saladin compared Raynald with the king of Ethiopia who had tried to destroy Mecca in 570 and was called the "Elephant" in the Surah Fil of the Quran.[127] Ibn al-Athir described him as "one of the most devilish of the Franks, and one of the most demonic", adding that Raynald "had the strongest hostility to the Muslims".[128] Islamic extremists still regard Raynald as a symbol of their enemies: one of the two mail bombs hidden in a cargo aircraft in 2010 was addressed to "Reynald Krak" in clear reference to him.[7]

Most Christian authors who wrote of Raynald in the 12th and 13th centuries were influenced by Raynald's political opponent, William of Tyre.[124] The author of the Estoire d'Eracles stated that Raynald's attack against a caravan at the turn of 1186 and 1187 was the "reason of the loss of the Kingdom of Jerusalem".[74] Modern historians have usually also treated Raynald as a "maverick who did more harm to the Christian than to the [Muslim] cause".[124] Runciman describes him as a marauder who could not resist the temptation presented by the rich caravans passing through Oultrejordain.[53] He argues that Raynald attacked a caravan during the 1180 truce because he "could not understand a policy that ran counter to his wishes".[53] Cobb introduces Raynald as the "[r]elentless nemesis of Saladin", adding that Raynald's provocative actions inevitably led to Saladin's fatal invasion against the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[129] Along with Guy of Lusignan and the Knights Templar, Raynald is one of the negative characters in the Kingdom of Heaven, an epic action movie directed by Ridley Scott and released in 2005. Portrayed by Brendan Gleeson,[130] Raynald is presented in the film as an aggressive Christian fanatic who deliberately provokes a conflict with the Muslims to achieve their total destruction.[131]

Some Christian authors regarded Raynald as a martyr for the faith.[85] After learning of Raynald's death from King Guy's brother Geoffrey of Lusignan, Peter of Blois dedicated a book (entitled Passion of Prince Raynald of Antioch) to him shortly after his death. The Passion underlines that Raynald defended the True Cross at Hattin. [85] Among modern historians, Hamilton portrays Raynald as "an experienced and responsible crusader leader" who made several attempts to prevent Saladin from uniting the Muslim realms along the borders of the crusader states.[132] His comments are described by Cobb as "attempts to dispel" Raynald's "bad press".[133] The historian Alex Mallett refers to Raynald's naval expedition as "one of the most extraordinary episodes in the history of the Crusades, and yet one of the most overlooked".[128] In 2017, the journalist Jeffrey Lee published a biography about Raynald, entitled God's Wolf,[note 1] presenting him, according to the historian John Cotts,[134] in a nearly hagiographic style as a loyal, valiant, and talented warrior. Lee's book was praised by James Delingpole—a blogger associated with Breitbart—who attributed Raynald's bad reputation in the Western world to "cultural self-hatred",[135] but historians such as Matthew Gabriele sharply criticised Lee's approach. Gabriele concludes that Lee's book "does violence to the study of the past" due to his uncritical use of primary sources and his obvious attempt to make a connection between medieval history and 21st-century politics.[136]

Notes[editar]

References[editar]

- ↑ a b c Hamilton, 2000, p. 104.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 201.

- ↑ a b Runciman, 1989, p. 345.

- ↑ Richard, 1989, pp. 410, 416.

- ↑ Richard, 1989, pp. 412–413.

- ↑ Richard, 1989, p. 410.

- ↑ a b Cotts, 2021, p. 43.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, pp. 4–25.

- ↑ a b c d Barber, 2012, p. 206.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, pp. 180–185.

- ↑ a b Hamilton, 2000, p. 98.

- ↑ a b Hamilton, 1978, p. 98 (note 8).

- ↑ Barber, 2012, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Lock, 2006, pp. 40, 50.

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, pp. 330–332, 345.

- ↑ Buck, 2017, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ a b Buck, 2017, p. 78.

- ↑ Buck, 2017, p. 228.

- ↑ a b c d Hamilton, 1978, p. 98.

- ↑ a b Runciman, 1989, p. 358.

- ↑ Baldwin, 1969, p. 546.

- ↑ a b Runciman, 1989, p. 365.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, pp. 82, 98, 103.

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, p. 408.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 365.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, p. 112.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, p. 105.

- ↑ a b Hamilton, 1978, p. 99.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 264.

- ↑ a b Hamilton, 2000, p. 111.

- ↑ Lock, 2006, p. 63.

- ↑ a b c Hamilton, 2000, p. 117.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, p. 100 (note 22).

- ↑ Baldwin, 1969, p. 593 (note 2).

- ↑ a b Barber, 2012, p. 268.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, p. 118.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, pp. 268–269.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, p. 123.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, p. 133.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, pp. 270–271.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, p. 100 (note 24).

- ↑ The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin, p. 54.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, p. 101 (note 25).

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, p. 101 (note 26).

- ↑ a b Barber, 2012, p. 275.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, p. 101.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, p. 101 (note 27).

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 277.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, p. 101 (note 29).

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 276.

- ↑ a b Hamilton, 1978, p. 102.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, p. 103 (note 39).

- ↑ a b c Runciman, 1989, p. 431.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ a b Hamilton, 2000, p. 171.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, pp. 171–172.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, p. 103 (note 42).

- ↑ Lock, 2006, pp. 61, 66.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, p. 103.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 278.

- ↑ a b c Barber, 2012, p. 284.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, p. 180.

- ↑ Mallett, 2008, p. 142.

- ↑ Mallett, 2008, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ a b Runciman, 1989, p. 437.

- ↑ Mallett, 2008, p. 143.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, p. 181.

- ↑ Baldwin, 1969, p. 599.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 281.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 282.

- ↑ a b Runciman, 1989, p. 440.

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, pp. 440–441.

- ↑ a b c d Runciman, 1989, p. 441.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Hamilton, 2000, p. 225.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 289.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, pp. 289–290, 293.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, p. 218.

- ↑ Baldwin, 1969, p. 604.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, p. 220.

- ↑ a b Barber, 2012, p. 294.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, pp. 294–295.

- ↑ a b Baldwin, 1969, p. 605.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 295.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Hamilton, 1978, p. 107.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ a b c d Barber, 2012, p. 297.

- ↑ a b Runciman, 1989, p. 450.

- ↑ Baldwin, 1969, p. 606.

- ↑ Cobb, 2016, p. 185.

- ↑ The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from Al-Kamil Fi'l-Ta'rikh, pp. 316–317 (s.a. 582).

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, p. 454.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, p. 227.

- ↑ a b Hamilton, 2000, p. 229.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 299.

- ↑ Baldwin, 1969, p. 610.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 300.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 301.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, p. 304.

- ↑ a b c d Barber, 2012, p. 306.

- ↑ a b c d e f Runciman, 1989, p. 459.

- ↑ Cotts, 2021, p. 42.

- ↑ Mallett, 2014, p. 72 (note 49).

- ↑ a b Nicholson, 1973, p. 162.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, pp. 306, 423.

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, p. 460.

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, p. 183, Appendix III (Genealogical tree No. 2).

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, p. 183.

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, p. 199.

- ↑ Buck, 2017, p. 79.

- ↑ Makk, 1994, pp. 47, 91.

- ↑ a b Makk, 1994, p. 47.

- ↑ Makk, 1994, p. 91.

- ↑ Chiappini, 2001, p. 31.

- ↑ Buck, 2017, p. 83.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2000, pp. xviii, 40–41.

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, p. 365, Appendix III (Genealogical tree No. 2).

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, p. 413.

- ↑ a b Hamilton, 2000, p. 90.

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, p. 335 (note 1), Appendix III (Genealogical tree No. 4).

- ↑ Runciman, 1989, p. 441 (note 1).

- ↑ a b Hamilton, 2000, p. 92.

- ↑ Baldwin, 1969, p. 592 (note 592).

- ↑ a b c Hamilton, 1978, p. 97.

- ↑ The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin, p. 37.

- ↑ Barber, 2012, pp. 306, 423, 435.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, p. 97 (note 1).

- ↑ a b Mallett, 2008, p. 141.

- ↑ Cobb, 2016, pp. xx, 185.

- ↑ Gabriele, 2018, p. 613.

- ↑ Liu, 2017, p. 89.

- ↑ Hamilton, 1978, pp. 102, 104–106.

- ↑ Cobb, 2016, p. 306 (note 31).

- ↑ Cotts, 2021, p. 52.

- ↑ Delingpole, 2018.

- ↑ Gabriele, 2018, p. 612.

Sources[editar]

Primary sources[editar]

- The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from Al-Kamil Fi'l-Ta'rikh (Part 2: The Years 541–582/1146–1193: The Age of Nur ad-Din and Saladin) (Translated by D. S. Richards) (2007). Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-4078-3.

- The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin or al-Nawādir al-Sultaniyya wa'l-Maḥāsin al-Yūsufiyya by Bahā' ad-Dīn Yusuf ibn Rafi ibn Shaddād (Translated by D. S. Richards) (2001). Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-0143-2.

Secondary sources[editar]

- Baldwin, Marshall W. (1969). «The Latin States under Baldwin III and Amalric I, 1143–1174; The Decline and Fall of Jerusalem, 1174–1189». En Baldwin, Marshall W., ed. The First Hundred Years. A History of the Crusades I. The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 528-561, 590-621. ISBN 978-0-2990-4834-1. Parámetro desconocido

|orig-year=ignorado (ayuda) - Barber, Malcolm (2012). The Crusader States. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-3001-1312-9.

- Buck, Andrew D. (2017). The Principality of Antioch and Its Frontiers in the Twelfth Century. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-7832-7173-3.

- Chiappini, Luciano (2001). Gli Estensi: Mille anni di storia [The Este: A Thousand Years of History] (en italiano). Corbo Editore. ISBN 978-8-8826-9029-8.

- Cobb, Paul M. (2016). The Race for Paradise: An Islamic History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1987-8799-0. Parámetro desconocido

|orig-year=ignorado (ayuda) - Cotts, John D. (2021). «Oppressor, Martyr, and Hollywood Villain: Reynald of Châtillon and the Representation of Crusading Violence». En Horswell, Mike; Skottki, Kristin, eds. The Making of Crusading Heroes and Villains. Engaging the Crusades: The Memory and Legacy of the Crusades 4. Routledge. pp. 42-59. ISBN 978-0-3672-6444-4.

- Delingpole, James (28 July 2018). «Why Have We Forgotten the Greatest of All Crusaders?». The Spectator (The Spectator (1828) Ltd). ISSN 2059-6499.

- Gabriele, Matthew (Fall 2018). «Book Review. God's Wolf: The Life of the Most Notorious of All Crusaders, Scourge of Saladin. By Jeffrey Lee.». En Spall, Richard, ed. The Historian (Taylor and Francis) 80 (3): 332. ISSN 0018-2370. doi:10.1111/hisn.12980.

- Hamilton, Bernard (1978). «The Elephant of Christ: Reynald of Châtillon». En Baker, Derek, ed. Studies in Church History (Cambridge University Press) 15 (15: Religious Motivation: Biographical and Sociological Problems for the Church Historian): 97-108. ISSN 0424-2084. S2CID 163740720. doi:10.1017/S0424208400008950.

- Hamilton, Bernard (2000). The Leper King and His Heirs: Baldwin IV and the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5216-4187-6.

- Lock, Peter (2006). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge Companions to History. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4153-9312-6.

- Liu, Yiou (2017). «Kingdom of Heaven and Its Ideological Message». Cinej Cinema Journal (University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh) 6 (1): 85-93. ISSN 2159-2411. doi:10.5195/cinej.2017.158.

- Makk, Ferenc (1994). «Anna (1.); Béla III». En Kristó, Gyula; Engel, Pál; Makk, Ferenc, eds. Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9–14. század) [Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th centuries)] (en húngaro). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 47, 91-92. ISBN 978-9-6305-6722-0.

- Mallett, Alex (2008). «A Trip down the Red Sea with Reynald of Châtillon». Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Cambridge University Press) 18 (2): 141-153. ISSN 1356-1863. S2CID 162979332. doi:10.1017/S1356186307008024.

- Mallett, Alex (2014). Popular Muslim Reactions to the Franks in the Levant, 1097–1291. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-3170-7798-5.

- Morton, Nicholas (2020). The Crusader States and their Neighbours: A Military History, 1099–1187. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1988-2454-1.

- Nicholson, Robert Lawrence (1973). Joscelyn III and the Fall of the Crusader States, 1154–1199. Brill. ISBN 978-9-0040-3676-5.

- Richard, Jean (1989). «Aux origines d'un grand lignage: Des Palladii à Renaud de Châtillon» [On the Origins of a Great Lineage: From the Palladii to Raynald of Châtillon]. Media in Francia: Recueil de mélanges offert à Karl Ferdinand Werner à l'occasion de son 65e anniversaire par ses amis et collègues français [Media in France: A Collection of Various Studies Offered to Karl Ferdinand Werner on the Occasion of his 65th birthday by his French Friends and Colleagues]. Hérault-Éditions. pp. 409-418. ISBN 978-2-9038-5157-6.

- Runciman, Steven (1989). The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. A History of the Crusades II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5210-6163-6. Parámetro desconocido

|orig-year=ignorado (ayuda)

Further reading[editar]

- Hamilton, Bernard (2006). «Reynald of Châtillon». En Murray, Alan V., ed. Q–Z. The Crusades: An Encyclopedia IV. ABC-CLIO. p. 1027. ISBN 978-1-5760-7862-4.

- Hillenbrand, Carole (2003). «Some reflections on the imprisonment of Reynald of Châtillon». En Robinson, Chase F., ed. Texts, Documents and Artefacts: Islamic Studies in Honour of D.S. Richards. Brill. pp. 79-102. ISBN 978-9-0041-2864-4.

- Maalouf, Amin (1984). The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. Al Saqi Books. ISBN 978-0-8052-0898-6. (requiere registro).

- Man, John (2015). Saladin: The Life, the Legend and the Islamic Empire. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4735-0854-5.

- Schlumberger, Gustave (1898). Renaud de Chatillon, Prince d'Antioche, seigneur de la terre d'Outre-Jourdain [Raynald of Châtillon, Prince of Antioch, Lord of the Land of Outrejourdain]. Librairie Plon.

Error en la cita: Existen etiquetas <ref> para un grupo llamado «nota», pero no se encontró la etiqueta <references group="nota"/> correspondiente.