Usuario:Bill Holt/Taller

El canto de Sacred Harp es una tradición de música coral sagrada que originó en Nueva Inglaterra, y que luego se perpetuó y se continuó en el Sur de Estados Unidos. El nombre se derive de The Sacred Harp (El harpa sagrada), un libro de canciones ubicuo e historicamente importante impreso en notas de forma (en inglés: shape notes. La obra se publicó por primera vez en 1844 y se ha reaparecido en ediciones múltiples desde aquel tiempo. La música de Sacred Harp representa un ramo de una tradición de música estadounidense más antigua que se desarrollo durante el periodo de 1770 a 1820 de raices en Nueva Inglaterra, con un significante desarrollo relacionado bajo la influencia de servicios de renacimiento durante la década 1840-1850. Esta música se incluía en y se hizo profundamente asociada con libros de canciones que utilizaban el estilo de notación de música de notas de forma (en inglés: shape note), lo que fue popular en Estados Unidos en el siglo 18 y el siglo 19 temprano.[1]

La música de Sacred Harp se realiza de manera a cappella (solo voces, sin instrumentos), y se originó como música protestante (en inglés: Protestant music).

La música y su notación[editar]

El nombre de la tradición se derive del título del libro de notas de forma de la que se canta la música, The Sacred Harp. Actualmente este libro existe en varias ediciones, las que se describen más adelante.

En la música de notas de forma, las notas se imprimen con formas especiales que ayudan al lector a identificarlas en la escala musical. Hay dos sistemas prevalentes, uno que utiliza cuatro formas, y otro que utiliza siete formas. En el sistema de cuatro formas utilizado en The Sacred Harp, cada una de las cuatro formas se conecta a cierta sílaba, fa, sol, la, o mi, y estas sílabas se emplean para cantar las notas[2], igual que en el sistema más conocido que utiliza do, re, mi, etc. (véase solfeo). El sistema de cuatro formas puede cubrir la escala musical completa porque cada combinació sílaba-forma exepto mi se asigna a dos notas distintas de la escala. Por ejemplo, la escala Do Mayor se sería anotado y cantado de la siguiente manera:

La forma de fa es un triángulo, la de sol es un óvalo, la de la es un rectángulo, y la de mi es un diamante.

En el canto de Sacred Harp, el tono no es absoluto. Las formas y las notas designan grados de la escala, y no tonos específicos. Por eso, para una cancion en la clave de Do, fa designa Do y Fa; para una cancion en la clave de Sol, fa designa Sol y Do; así que se llama un sistema de do móvil.

Cuando los cantantes de Sacred Harp empiezan una canción, suelen comenzar por cantarla con la sílaba adecuada para cada tono, utilizando las formas para guiarse. Para los del grupo que aún no saben la canción, las formas les ayudan en la tarea de leer a primera vista. El proceso de leer a través de la canción con las formas también ayuda a fijar las notas en la memoria. Después de haber cantado las notas, el grupo canta los versos de la canción con la letra impresa.

Cantar la música Sacred Harp[editar]

Los grupos de cantar Sacred Harp siempre cantan a cappella, es decir, sin acompañamiento de instrumentos.[3][4] Los cantantes se disponen en un cuadrado vacío, con filas de asientos o de bancos en cada lado asignado a una de las cuatro voces: tiple, alto, tenor y bajo. Las voces de tiple y de tenor suelen ser mezclados, con voces cantando en distintas octavas.

No hay un solo director o conductor; al contrario, los participantes se turnan en conducir las canciones. La persona a que le toca conducir elige una canción del libro, y la "llama" por su número de página. Se suele conducir con la mano abierta, estando parado en el centro del cuadrado con cara hacia los tenores.

La altura a la que se canta la música es relativa; no hay ningún instrumento que pueda darles a los cantantes un punto de empezar. El conductor de turno, o algún otro cantante a que se le ha dado la tarea, encuentra una altura adecuada con qué empezar y la entona al grupo. Los cantantes responden con las notas iniciales de su parte, y entonces la canción empieza inmediatamente.

Por lo general la música no se canta exactamente como está impresa en el libro, sino con ciertas desviaciones establecidas por la costumbre.

Como implica el nombre, la música Sacred Harp es música sacra y originó como música cristiana protestante. Muchas de las canciones en el libro son himnos que usan palabras, métricas, y formas de estrofa que se usan en otros géneros de la himnología protestante. Sin embargo, las canciones de Sacred Harp son muy diferentes de los himnos protestantes convencionals en cuanto al estilo musical: algunas canciones, que se conocen como canciones de fuga, contienen secciones de textura polifónicas, y la armonía suele desenfatizar el intervalo de tercera a favor de los de cuarta y de quinta. En sus melodías, a menudo las canciones utilizan la escala pentatónica u otra escala que contiene menos de siete notas.

En cuanto a su forma musical, las canciones de Sacred Harp se agrupan en tres tipos. Muchas son canciones de himno, compuestos por lo general en frases de cuatro compases y cantado con dos o mas versos. Las canciones de fuga contienen una sección prominante que empieza aproximadamente 1/3 desde el inicio en la que las cuatro voces corales entra en sucesión, en la manera de una fuga. Los cánticos son canciones más largas, menos regular de forma de música o de letra, y que se cantan solamente una vez en lugar de en dos o más versos.[5]

<ref>La armonía y la forma de la música Sacred Harp se describe en {{harvnb|Cobb|1978|loc=ch. 2}}{{incomplete short citation|date=August 2021}} y con detalles más técnicos en {{harvnb|Horn|1970}}.</ref>

Lugares para cantar[editar]

El canto de Sacred Harp generalmente no sucede en los servicios de la iglesia, sino en reuniones especiales o "cantos" organizados para el propósito. Los cantos pueden ser locales, regionales, estatales, o nacionales. A menudo los cantos pequeños se llevan a cabo en hogares, con quizás solo una docena de personas. Algunos de los cantos grandes han tenido más de mil participantes. Los cantos más ambiciosos incluyen una cena compartida en el medio del día, tradicionalmente llamada "cena en el terreno" (en inglés: dinner on the grounds).

Algunos de los cantos más grandes y más antiguos se denominan "convenciones". La convencion de Sacred Harp más antigua era la Convención Musical Sureña, organizada en el Condado de Upson, Georgia en 1845. Las dos convenciones existentes más antiguas son la Convención Musical de Chattahoochee (organizada en el Condado de Coweta, Georgia en 1852), y la Convención de Sacred Harp de Tejas Oriental (organizada como la Convención Musical de Tejas Oriental en 1855).

La música de Sacred Harp como música participativa[editar]

Los cantantes de Sacred Harp perciben su tradición como una tradición participativa, y no pasiva. Los que se reúnen para un canto cantan para sí mismos y para los otros cantantes, y no para una audiencia. Eso se lo puede observar en varios aspectos de la tradición.

Primero, la disposición de los asientos (las cuatro voces en un cuadrado mirando al centro) está claramente destinada a los cantantes, no a los oyentes externos. Las personas que no son cantantes siempre son bienvenidas a asistir a un canto, pero generalmente se sientan entre los cantantes en las últimas filas de la sección de tenores, en lugar de en un lugar de audiencia separado designado.

La person a quien le toca conducir, al estar equidistante de todas las secciones, en principio escucha el mejor sonido. La experiencia sonora a menudo intensa de estar parado en el centro del cuadrado se considera uno de los beneficios de conducir, y a veces se le invita a un invitado como cortesía a pararse junto al conductor de turno durante una canción.

La música en sí también pretende ser participativa. La mayoría de las formas de composición coral colocan la melodía en las voces más agudas (soprano), donde la audiencia puede escucharla major, con las otras partes escritas para no oscurecer la melodía. Por el contrario, los compositores de Sacred Harp se han propuesto hacer que cada parte musical sea cantable e interesante por derecho propio, dando así a cada cantante del grupo una tarea absorbente.[6] Por esta razón, "realzar la melodía" no es una prioridad alta en la composición de Sacred Harp y, de hecho, se acostumbra asignar la melodía no a los tiples sino a los tenores. Las canciones de fuga, en las que cada sección tiene su momento para brillar, también ilustran la importancia en Sacred Harp de mantener la independencia de cada parte vocal.

History of Sacred Harp singing[editar]

Marini (2003) rastrea las raíces más tempranas de Sacred Harp hasta la "música parroquial rural" de la Inglaterra de principios del siglo XVIII. Esta forma de música de iglesia rural evolucionó una serie de rasgos distintivos que se transmitiron de tradición en tradición, hasta que por fin se convirtieron en parte del canto de Sacred Harp. Estos rasgos incluían la asignación de la melodía a los tenores, la estructura armónica que enfatiza la cuartas y las quintas, y la distinción entre el himno ordinaro de cuatro partes ("canción sencilla"), el cántico, y la canción de fuga. Varios compositores de esta escuela, incluso Joseph Stephenson y Aaron Williams, se representan en la edición de 1991 de The Sacred Harp. Para más información sobre la historia de las raíces inglesas de la música de Sacred Harp, véase West gallery music.[7]

Around the mid-18th century, the forms and styles of English country parish music were introduced to America, notably in a new tunebook called Urania, published 1764 by the singing master James Lyon.[8] This stimulus soon led to the development of a robust native school of composition, signaled by the 1770 publication of William Billings's The New England Psalm Singer, and then by a great number of new compositions by Billings and those who followed in his path. The work of these composers, sometimes called the "First New England School", forms a major part of the Sacred Harp to this day.

Billings and his followers worked as singing masters, who led singing schools. The purpose of these schools was to train young people in the correct singing of sacred music. This pedagogical movement flourished, and led ultimately to the invention of shape notes, which originated as a way to make the teaching of singing easier. The first shape note tunebook appeared in 1801: The Easy Instructor[9] by William Smith and William Little. At first, Smith and Little's shapes competed with a rival system, created by Andrew Law (1749–1821) in his The Musical Primer of 1803. Although this book came out two years later than Smith and Little's book, Law claimed earlier invention of shape notes. In his system, a square indicated fa, a circle sol, a triangle la and a diamond, mi. Law used the shaped notes without a musical staff. The Smith and Little shapes ultimately prevailed.

Shape notes became very popular, and during the first part of the nineteenth century, a whole series of shape note tunebooks appeared, many of which were widely distributed. As the population spread west and south, the tradition of shape note singing expanded geographically. Composition flourished, with the new music often drawing on the tradition of folk song for tunes and inspiration. Probably the most successful shape note book prior to The Sacred Harp was William Walker's Southern Harmony, published in 1835 and still in use today.[10]

Even as they flourished and spread, shape notes and the kind of participatory music which they served came under attack. The critics were from the urban-based "better music" movement, spearheaded by Lowell Mason, which advocated a more "scientific" style of sacred music, more closely based on the harmonic styles of contemporaneous European music. The new style gradually prevailed. Shape notes and their music disappeared from the cities prior to the Civil War, and from the rural areas of the Northeast and Midwest in the following decades. However, they retained a haven in the rural South, which remained a fertile territory for the creation of new shapenote publications.[11]

The arrival of The Sacred Harp[editar]

Sacred Harp singing came into being with the 1844 publication of Benjamin Franklin White and Elisha J. King's The Sacred Harp. It was this book, now distributed in several different versions, that came to be the shape note tradition with the largest number of participants.

B. F. White (1800–1879) was originally from Union County, South Carolina, but since 1842 had been living in Harris County, Georgia. He prepared The Sacred Harp in collaboration with a younger man, E. J. King, (ca. 1821–44), who was from Talbot County, Georgia. Together they compiled, transcribed, and composed tunes, and published a book of over 250 songs.

King died soon after the book was published, and White was left to guide its growth. He was responsible for organizing singing schools and conventions at which The Sacred Harp was used as the songbook. During his lifetime, the book became popular and would go through three revisions (1850, 1859, and 1869), all produced by committees consisting of White and several colleagues working under the auspices of the Southern Musical Convention. The first two new editions simply added appendices of new songs to the back of the book. The 1869 revision was more extensive, removing some of the less popular songs and adding new ones in their places. From the original 262 pages, the book was expanded by 1869 to 477. This edition was reprinted and continued in use for several decades.

Origin of the modern editions[editar]

Around the turn of the 20th century, Sacred Harp singing entered a period of conflict over the issue of traditionalism. The conflict ultimately split the community.[12]

B. F. White had died in 1879 before completing a fourth revision of his book; thus the version that Sacred Harp participants were singing from was by the turn of the century over three decades old. During this time, the musical tastes of Sacred Harp's traditional adherents, the inhabitants of the rural South, had changed in important ways. Notably, gospel music – syncopated and chromatic, often with piano accompaniment – had become popular, along with a number of church hymns of the "mainstream" variety, such as "Rock of Ages". Seven-shape notation systems had appeared and won adherents away from the older four-shape system (see shape note for details). As time passed, Sacred Harp singers doubtless became aware that what they were singing had become quite distinct from contemporary tastes.

The natural path to take—and the one ultimately taken—would be to assert the archaic character of Sacred Harp as an outright virtue. In this view, Sacred Harp should be treasured as a time-tested musical tradition, standing above current trends of fashion. The difficulty with adopting traditionalism as a guiding doctrine was that different singers had different opinions about just what form the stable, traditionalized version of Sacred Harp would take.

The first move was made by W. M. Cooper, of Dothan, Alabama, a leading Sacred Harp teacher in his own region, but not part of the inner circle of B. F. White's old colleagues and descendants. In 1902 Cooper prepared a revision of The Sacred Harp that, while retaining most of the old songs, also added new tunes that reflected more contemporary music styles.[13] Cooper made other changes, too:

- He retitled many old songs. These songs were formerly named by their tune, using arbitrarily chosen place names ("New Britain", "Northfield", "Charlestown"). The new names were based on the text; thus "New Britain" became "Amazing Grace", "Northfield" became "How Long, Dear Savior", and so on. The old system was intended in colonial times to permit mixing and matching of tunes and texts, but was unnecessary in a system where the pairing of tune and text was fixed.

- He transposed some songs into new keys. This is thought to have brought the notation closer to actual performing practice.

- He wrote new alto parts for the many songs that originally just had three vocal lines.

The Cooper revision was a success, being widely adopted in many areas of the South, such as Florida, southern Alabama, and Texas, where it has continued as the predominant Sacred Harp book to this day. The "Cooper book", as it is now often called, was revised by Cooper himself in 1907 and 1909. His son-in-law published the book in 1927, including an appendix compiled by revision committee. The Sacred Harp Book Company was formed in 1949, and subsequent revision has been supervised by editorial committees under its instruction. New editions were issued in 1950, 1960, 1992, 2000, 2006 and 2012.

In the original core geographic area of Sacred Harp singing, northern Alabama and Georgia, the singers did not in general take to the Cooper book, as they felt it deviated too far from the original tradition. Obtaining a new book for these singers was made more difficult by the fact that B. F. White's son James L. White, who would have been the natural choice to prepare a new edition, was a non-traditionalist. His "fifth edition" (1909)[14] won little support among singers, while his "fourth edition with supplement" (1911) enjoyed some success in a few areas.[15] Ultimately, a committee headed by Joseph Stephen James produced an edition entitled Original Sacred Harp (1911) that largely satisfied the wishes of this community of singers.[16]

The James edition was further revised in 1936 by a committee under the leadership of the brothers Seaborn and Thomas Denson, both influential singing school teachers. Both died shortly before the project was complete, and the remaining work was overseen by Paine Denson, son of Thomas. This book was entitled Original Sacred Harp, Denson Revision, and was itself revised 1960, 1967, and 1971;[17] a more thorough revision and remodeling of this book, overseen by Hugh McGraw, is known simply as the "1991 Edition", though some singers still call it the "Denson book".

Even the highly traditionalist James and Denson books followed Cooper in adding alto parts to most of the old three-part songs (these alto parts led to an unsuccessful lawsuit by Cooper).[18] Some people (see for instance the reference by Buell Cobb given below) believe that the new alto parts imposed an esthetic cost by filling in the former stark open harmonies of the three-part songs. Wallace McKenzie argues to the contrary, basing his view on a systematic study of representative songs.[19] In any event, there is little support today for abandoning the added alto parts, since most singers give a high priority to giving every side of the square its own part to sing.

It was thus that the traditionalism debate split the Sacred Harp community, and there seems little prospect that it will ever reunite under a single book. However, there have been no further splits. Both the Denson and the Cooper groups adopted traditionalist views for the particular form of Sacred Harp they favored, and these forms have now been stable for about a century.

The strength of traditionalism can be seen in the front matter of the two hymnbooks. The Denson book is forthrightly Biblical in its defense of tradition:

DEDICATED TO

All lovers of Sacred Harp Music, and to the memory of the illustrious and venerable patriarchs who established the Traditional Style of Sacred Harp singing and admonished their followers to "seek the old paths and walk therein".[20]

The Cooper book also shows a warm appreciation of tradition:

May God bless everyone as we endeavor to promote and enjoy Sacred Harp music and to continue the rich tradition of those who have gone before us.

To say that both communities are traditionalist does not mean they discourage the creation of new songs. To the contrary, it is part of the tradition that musically creative Sacred Harp singers should become composers themselves and add to the canon. The new compositions are prepared in traditional styles, and could be considered a kind of tribute to the older material. New songs have been incorporated into editions of The Sacred Harp throughout the 20th century.

Other Sacred Harp books[editar]

Two other books are currently used by Sacred Harp singers. A few singers in north Georgia employ the "White book", an expanded version of the 1869 B. F. White edition edited by J. L. White. African–American Sacred Harp singers, although primarily users of the Cooper book, also make use of a supplementary volume, The Colored Sacred Harp, produced by Judge Jackson (1883–1958) in 1934 and later revised in two subsequent editions. In his book Judge Jackson and The Colored Sacred Harp, Joe Dan Boyd identified four regions of Sacred Harp singing among African–Americans: eastern Texas (Cooper book), northern Mississippi (Denson book), south Alabama and Florida (Cooper book), and New Jersey (Cooper book). The Colored Sacred Harp is limited to the New Jersey and south Alabama–Florida groups. Sacred Harp was "exported" from south Alabama to New Jersey. It appears to have died out among the African–Americans in eastern Texas.

In summary, three revisions of and one companion book to The Sacred Harp are currently in use in Sacred Harp singing:

- The Sacred Harp, 1991 edition (the "Denson book"). Carrollton, Georgia: Sacred Harp Publishing Company.

- The Sacred Harp, Revised Cooper Edition, 2012. Samson, Aabama: The Sacred Harp Book Company.

- The Sacred Harp, J. L. White Fourth Edition, with Supplement (the "White book"). Atlanta, Georgia: J. L. White. Released 1911; republished 2007.

- The Colored Sacred Harp. Ozark, Alabama: Judge Jackson. [3rd revised edition (1992) includes rudiments by H. J. Jackson (son of J. Jackson) and an autobiography of Judge Jackson].

Sacred Harp books generally contain a section on rudiments, describing the basics of music and Sacred Harp singing.

The spread of Sacred Harp singing in modern times[editar]

In recent years, Sacred Harp singing has experienced a resurgence in popularity, as it is discovered by new participants who did not grow up in the tradition.[21] New singers typically strive to follow the original southern customs at their singings. Traditional singers have responded to this need by providing help in orienting the newcomers. For instance, the Rudiments section of the 1991 Denson edition includes information on how to hold a singing; this information would be superfluous in a traditional context, but is important for a group starting up on its own. The tradition of the singing master is still carried on today, and singing masters from traditional Sacred Harp regions often travel outside the South to teach. In recent years an annual summer camp has been established, at which newcomers can learn to sing Sacred Harp.[22]

The U.S. beyond the South[editar]

There are now strong Sacred Harp singing communities in most major urban areas of the United States, and in many rural areas, as well.[23] One of the first groups of singers formed outside the traditional Southern home region of Sacred Harp singing was in the Chicago area.[24] The first Illinois convention was held in 1985, with enthusiastic and strongly proactive support by prominent Southern traditional singers.[24] The Midwest Convention is now acknowledged to be one of the major American conventions, attracting hundreds of singers from all over the US and abroad.[24] Similarly, the Sacred Harp singing community in western New England has become a prominent one in recent years; the late songleader Larry Gordon has been credited with re-popularizing Sacred Harp singing in northern New England.[25] In March 2008, the 2008 Western Massachusetts Sacred Harp Convention attracted over 300 singers from 25 states and a number of foreign countries.[26] Other prominent singing conventions outside the South include, for example, the Keystone Convention in Pennsylvania, the Missouri Convention, and the Minnesota State Convention, which began in 1990.[27]

Sacred Harp Singing beyond the US[editar]

In more recent times Sacred Harp singing has spread beyond the borders of the United States.

The United Kingdom has had an active Sacred Harp community since the 1990s. The first UK Sacred Harp convention took place in 1996.[28] There are regular singings in London,[29][30] the Home Counties, the Midlands, Yorkshire,[31] Lancashire, Manchester, Brighton,[32] Newcastle,[33] Durham,[34] southwest England,[35] Bristol,[36] as well as in Scotland.[37]

Canada has a decades-long tradition of Sacred Harp singing, particularly in Southern Ontario and the Eastern Townships of Quebec. Singings have been organized weekly in Montreal, Quebec since 2011, as well as a monthly afternoon sing, and the first Montreal all-day sing took place in the spring of 2016.[38] Sacred Harp singing has happened on a monthly basis for years in Toronto.

Australia has had Sacred Harp singing since 2001, and singings are held regularly in Melbourne,[39] Sydney,[40] Canberra[41] and Blackwood.[42] The first Australian All Day Singing was held in Sydney in 2012.[43]

In January 2009, Sacred Harp singing was introduced to Ireland, by Dr Juniper Hill of University College Cork, spreading quickly from a class module into the wider community. In March 2011 U.C.C. hosted the first annual Ireland Sacred Harp Convention, and the Cork community held their first All-Day Singing on 22 October 2011. There are now also growing Sacred Harp communities in Belfast and Dublin.[44]

In the most recent development, Sacred Harp singing has expanded beyond the limits of English-speaking countries to mainland Europe. In 2008 a singing community was established in Poland (which hosted the first Camp Fasola Europe in September 2012).[45] In Germany there are regular weekly or monthly singings in Bremen,[46] Hamburg,[47] Berlin,[48] Cologne[49] and Munich, most of them with their own annual All-Day singings. Elsewhere in Germany, singers meet irregularly in Frankfurt, Gießen and Nürnberg. Recently groups have started up in Amsterdam,[50] Paris and Clermont-Ferrand[51] Oslo, Norway, and Uppsala, Sweden.[52] Both the Swedish and Norwegian groups have arranged All Day Singings. The 6th Oslo All-Day Singing will in 2022 be arranged June 4.-5.

Regular singings are also taking place in Israel,[53] and in April, 2016, an all-day singing was held in Paris, France.[54]

Use in popular works[editar]

Sacred Harp singing appears as diegetic music in the films Cold Mountain (2004)[55][56] and Lawless (2012), and as background music in The Ladykillers (2004).[57]

The 2010 song "Tell Me Why" by M.I.A. includes a sample of "The Last Words of Copernicus" by Sarah Lancaster, recorded at the 1959 United Sacred Harp Convention in Fyffe, Alabama, by Alan Lomax.[58] The album version of Bruce Springsteen's "Death to My Hometown" (2012) also samples this recording.[59]

Electronic musician Holly Herndon's 2019 track "Frontier" includes a performance of Herndon's music by a singing class in Berlin, Germany.[60]

Origins of the music[editar]

The music used in Sacred Harp singing is eclectic. Most of the songs can be assigned to one of four historical layers.

{{ | The oldest of these layers comes from 18th century New England, and represents a rendition in shape notes of the work of outstanding early American composers such as William Billings and Daniel Read, who worked as singing masters. | A second layer comes from the decades around 1830, following the migration of the shape note tradition to the rural South. Many of the songs in this layer are believed to be originally secular folk tunes, harmonized in parts and given religious lyrics. As one would expect from the folk origin of such music, it often emphasizes the notes of the pentatonic scale. They often employ stark, vivid harmonies based on open fifths. Most of the songs of this layer were originally composed in just three parts (treble, tenor, bass), with the altos added later, as noted above.

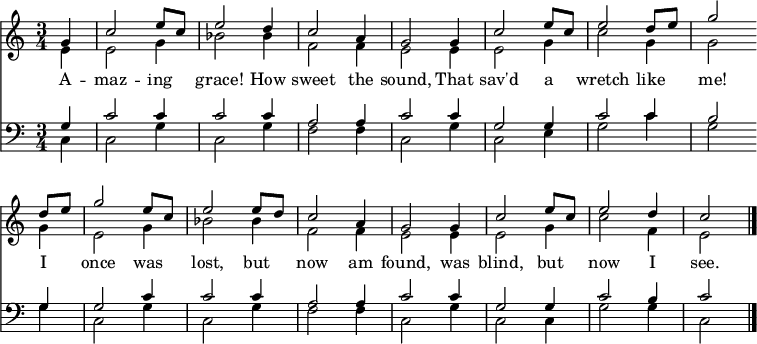

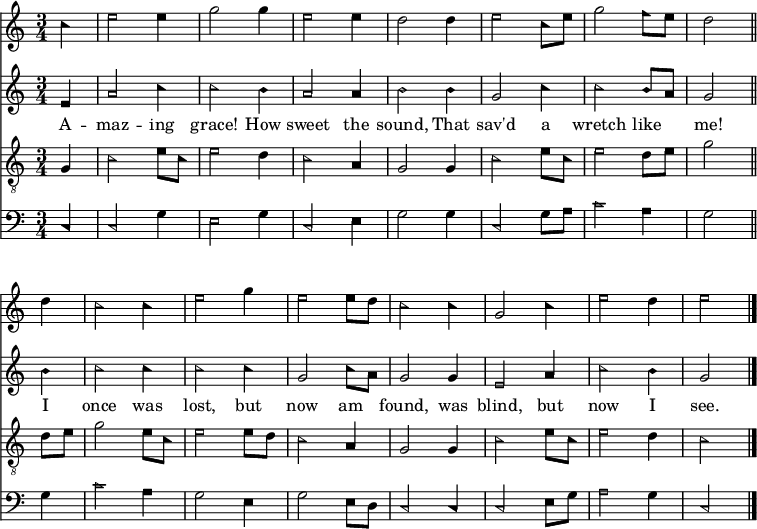

The sound of this musical layer, as well as to some extent The Sacred Harp in general, can be observed by comparing versions of the well-known hymn "Amazing Grace", which is familiar to many Americans in a form such as the following:

In The Sacred Harp (1991 edition), "Amazing Grace" is harmonized quite differently. Note that the "air", or melody, is in the tenor.

| A third layer of Sacred Harp music is from the mid nineteenth century and represents the popular sensibility of that era. A number of these mid-century works have an almost primal simplicity—the harmony is essentially a single extended major chord, and the parts a decoration in slow tempo of that chord. | The most recent layer consists of the songs that were added to the books during the twentieth century. These are the work of musically creative participants in the Sacred Harp tradition, who strove to create songs that would fit into the existing tradition by adopting the style of one of the earlier periods. About a sixth of the Denson edition is taken up with such compositions, dating from as recently as 1990. The twentieth-century composers often have recycled their lyrics from earlier Sacred Harp songs (or from their sources, such as the work of the 18th-century hymnodist Isaac Watts). A number of these modern compositions have become favorites of the singing community, and it is anticipated that future editions of The Sacred Harp will also include new songs. }}

There are a few additional songs in The Sacred Harp, 1991 edition that cannot be assigned to any of these four main layers. There are some very old songs of European origin, as well as songs from the English rural tradition that inspired the early New England composers. There are also a handful of songs by European classical composers (Ignaz Pleyel, Thomas Arne, and Henry Rowley Bishop).The book even includes five hymns by Lowell Mason, long ago the implacable enemy of the tradition that The Sacred Harp has preserved to this day.[61]

The description just given is based on The Sacred Harp, 1991 edition, also known as the Denson edition. The widely used "Cooper" edition overlaps considerably (about 60%) in content, but also includes many later songs. A detailed comparison of the two editions has been made by Sacred Harp scholar Gaylon L. Powell.[62]

Other books with the title Sacred Harp[editar]

The Sacred Harp was a popular name for 19th century hymn and tune books, with no fewer than four bearing the title. The first of these was compiled by John Hoyt Hickok and printed in Lewistown, Pennsylvania in 1832. The second was compiled by Lowell and Timothy Mason and printed in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1834, as part of the "better music" movement mentioned above. The publisher released their book as a shape note edition, while they preferred to urbanize their audience by releasing a round note edition.[63][64]

The third Sacred Harp was the one by B. F. White and E. J. King (1844), the origin of today's Sacred Harp singing tradition.

Lastly, according to W. J. Reynolds, writing in Hymns of Our Faith, there was yet a fourth Sacred Harp – The Sacred Harp published by J. M. D. Cates in Nashville, Tennessee in 1867.

Comedy -humour

In order to increase accessibility to the Sacred Harp tunes, Jo Puma - Wild Choir Music was published by the Machinists Union Press, combining the unaltered Sacred Harp arrangements with new secular lyrics by Secretary Michael.[65]

See also[editar]

- Awake, My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp

- Chattahoochee Musical Convention

- East Texas Musical Convention

- List of shape-note tunebooks

- Sacred Harp hymnwriters and composers

- Shape note

- Southwest Texas Sacred Harp Singing Convention

Notes[editar]

- ↑ David Warren Steel, "Shape-note hymnody", en Grove Music Online (Oxford University Press: artículo actualizado 16 octubre 2013) Se requiere suscripción

- ↑ Esta es una versión simplificada de la solmisación guidoniano que también se usaba en la Inglaterra isabelina: véase solfeo, Guido de Arezzo#Obra

- ↑ En particular, no hay harpas. A veces los cantantes piensan que la expresión "Sacred Harp" es una metáfora para la voz humana Anon., 1940, p. 127.

- ↑ En algunas grabaciones historicas tempranas, un piano o un órgano de salón acompaña los cantantes. En las décadas siguientes, el práctico de usar tales instrumentos se ha desaparecido.

- ↑ La armonía y la forma de la música Sacred Harp se describe en Cobb, 1978, ch. 2 y con detalles más técnicos en Horn, 1970.

- ↑ Horn, 1970, p. 86.

- ↑ Fuentes para este párrafo: Marini, 2003, p. 77, Temperley, 1983, y el ensayo "Distant Roots of Shape Note Music" por Keith Willard, publicado en el sitio web fasola.org (enlace roto disponible en este archivo)..

- ↑ Marini, 2003, p. 78.

- ↑ Dick Hulan writes, "My copy of William Smith's Easy Instructor, Part II (1803) attributes the invention [of shape notes] to 'J. Conly of Philadelphia'." According to David Warren Steel, in John Wyeth and the Development of Southern Folk Hymnody, "This notation was invented by Philadelphia merchant John Connelly, who on 10 March 1798 signed over his rights to the system to Little and Smith."[cita requerida] Andrew Law also laid claim to the invention of the shape note system.

- ↑ The shape note systems continued to evolve throughout the 19th century; for a more complete history, see shape note.

- ↑ Source for this paragraph: Marini, 2003, p. 81. Evidence that Americans outside the rural South were slow, even reluctant, to give up their old music is given in Horn, 1970, ch. 12.

- ↑ The primary source for this section is Cobb, 2001, ch. 4.

- ↑ Miller, 2004 characterizes Cooper book style thus: it "contains a greater proportion of "camp meeting" songs than the Denson book, with more compressed part-writing, chromatic harmonies, and choruses characterized by call-and-response rather than "fuging" style. Denson book singers generally say that the Cooper book sounds more like "new book or gospel singing".

- ↑ This edition may be viewed in digital form at [1] (enlace roto disponible en este archivo)..

- ↑ Cobb, 2001, pp. 98–110.

- ↑ Cobb, 2001, pp. 94–98.

- ↑ Cobb, 2001, pp. 110–117.

- ↑ Cobb, 2001, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ McKenzie, 1989 further judges that the Cooper alto parts were more successful than the Denson ones in retaining the original harmonic style.

- ↑ The passage quotes Jeremiah 6:16: "Thus saith the LORD, Stand ye in the ways, and see, and ask for the old paths, where is the good way, and walk therein, and ye shall find rest for your souls."

- ↑ For an extended narrative of this spread, see Bealle, 1997, ch. 4.

- ↑ Clawson, 2011.

- ↑ A guide to singings that demonstrates this dramatic spread may be found at the "fasola.org" web site, under http://fasola.org/singings/ (enlace roto disponible en este archivo)..

- ↑ a b c Miller, 2004

- ↑ Lueck, Ellen (2017). «Sacred Harp Singing in Europe: Its Pathways, Spaces, and Meanings». Dissertation. Consultado el 11 November 2021.

- ↑ «Sacred Harp sing draws followers». Archivado desde el original el 9 April 2016. Consultado el 31 March 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «22nd Annual Minnesota State Sacred Harp Singing Convention». Archivado desde el original el 3 March 2016. Consultado el 31 March 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Conventions». United Kingdom Sacred Harp & Shapenote Singing. Edwin and Sheila Macadam. Archivado desde el original el 4 August 2014. Consultado el 15 de mayo de 2014. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «London Sacred Harp». Archivado desde el original el 23 March 2016. Consultado el 31 March 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Music». London Sacred Harp. Archivado desde el original el 22 March 2016. Consultado el 31 March 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Sheffield & South Yorkshire Sacred Harp». Archivado desde el original el 14 April 2016. Consultado el 31 March 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Brighton Shape Note Singing». Archivado desde el original el 28 June 2016. Consultado el 31 March 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Newcastle Sacred Harp». Consultado el 23 January 2020.

- ↑ «Durham Sacred Harp». Consultado el 23 January 2020.

- ↑ «South West Shape Note (Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, Dorset and Wiltshire)». Consultado el 1 January 2020.

- ↑ «Bristol Sacred Harp». Archivado desde el original el 9 August 2016. Consultado el 19 June 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Shapenote Scotland». Archivado desde el original el 14 April 2016. Consultado el 31 March 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Montreal Sacred Harp Singers». Facebook. Consultado el 31 March 2016.

- ↑ «Facebook». Facebook. Consultado el 31 March 2016.

- ↑ «Facebook». Facebook. Consultado el 31 March 2016.

- ↑ «Facebook». Facebook. Consultado el 31 March 2016.

- ↑ «Blackwood Academy». Consultado el 31 March 2016.

- ↑ «Australia's First Ever Sacred Harp Singing Convention Hits Sydney». Timber and Steel. 17 September 2012. Archivado desde el original el 13 October 2016. Consultado el 31 March 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Cork Sacred Harp». Archivado desde el original el 14 April 2016. Consultado el 31 March 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Application form for Camp Fasola Europe». Archivado desde el original el 10 June 2013. Consultado el 30 April 2012. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Sacred Harp Bremen». Archivado desde el original el 28 March 2016. Consultado el 14 January 2020. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Sacred Harp Singing in Hamburg – Sacred Harp Hamburg Singing School – Home». Sacred Harp Singing in Hamburg. Archivado desde el original el 27 March 2016. Consultado el 31 March 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Sacred Harp Berlin». Sacred Harp Berlin (en inglés). Archivado desde el original el 28 September 2017. Consultado el 8 de marzo de 2018. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Sacred Harp Cologne». Sacred Harp Cologne. Archivado desde el original el 20 August 2018. Consultado el 8 de marzo de 2018. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Sacred Harp Amsterdam». Archivado desde el original el 17 November 2018. Consultado el 13 January 2019. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Sacred Harp Auvergne». Consultado el 31 March 2016.

- ↑ «406 and More, in Sweden». The Sacred Harp Publishing Company. 31 December 2015. Archivado desde el original el 20 March 2016. Consultado el 31 March 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Facebook». Facebook. Consultado el 31 March 2016.

- ↑ «Sacred Harp Paris – 1st All Day Singing». Consultado el 31 March 2016.

- ↑ Wurst, Nancy Henderson (4 January 2004). «'Cold Mountain' shows off sacred singing». Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ Burghart, Tara (13 February 2004). «Via 'Cold Mountain', old music is revived». The Boston Globe. Associated Press.

- ↑ «Sacred Harp in contemporary culture». Sacred Harp Australia. 16 August 2015. Consultado el 5 de mayo de 2019.

- ↑ Chris Tinkham (22 March 2012). «Bruce Springsteen: Wrecking Ball (Columbia) | Under the Radar – Music Magazine». undertheradarmag.com. Consultado el 10 August 2016.

- ↑ Plunkett, John; Karlsberg, Jesse P. (28 March 2012). «Bruce Springsteen's Sacred Harp Sample». The Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 1 (1).

- ↑ Gray, Julia (2 de mayo de 2019). «Holly Herndon – "Frontier"». Stereogum. Prometheus Global Media.

- ↑ See the online Index to the Denson edition: http://fasola.org/indexes/1991/?v=composer (enlace roto disponible en este archivo).

- ↑ L. Powell, Gaylon. «Comparison Tune Index». resources.texasfasola.org.

- ↑ Jackson (1933b, 395)

- ↑ Gould, 1853, p. 55.

- ↑ «Jo Puma - Wild Choir Music». machinistsunion.org. Consultado el 18 de octubre de 2021.

Sources[editar]

- Anon. (1940) Georgia: A guide to its towns and countryside. Compiled and written by workers of the Writers' Program of the Works Progress Administration. University of Georgia Press.

- Bealle, John (1997). Public Worship, Private Faith: Sacred Harp and American Folksong. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-1988-0.

- Clawson, Laura (15 September 2011). I Belong to This Band, Hallelujah!: Community, Spirituality, and Tradition Among Sacred Harp Singers. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-10959-6.

- Cobb, Buell E. (2001). The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music.

- Gould, Nathaniel Duren (1853). History of Church Music in America. Gould and Lincoln. p. 55.

- Horn, Dorothy D. (1970). Sing to me of Heaven: A Study of Folk and Early American Materials in Three Old Harp Books. University of Florida Press.

- Marini, Stephen A. (2003). Sacred Song in America: Religion, Music, and Public Culture. University of Illinois Press. See chapter 3, "Sacred Harp singing".

- McKenzie, Wallace (1989). «The Alto Parts in the 'True Dispersed Harmony' of The Sacred Harp Revisions». The Musical Quarterly (73): 153-171.

- Miller, Kiri (Winter 2004). «'First Sing the Notes': Oral and Written Traditions in Sacred Harp Transmission». American Music 22 (4): 475-501. JSTOR 3592990. doi:10.2307/3592990.

- Temperley, Nicholas (1983). The Music of the English Parish Church. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27457-9.

Further reading[editar]

- Boyd, Joe Dan (2002) Judge Jackson and The Colored Sacred Harp. Alabama Folklife Association. ISBN 0-9672672-5-0

See also the bibliographic entries under Shape note.

- Campbell, Gavin James (1997) " 'Old Can Be Used Instead of New': Shape-Note Singing and the Crisis of Modernity in the New South, 1880–1920." Journal of American Folklore 110:169–188.

- Cobb, Buell E. (1989). The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-2371-3.

- Cobb, Buell (2013). Like Cords Around My Heart: A Sacred Harp Memoir. Outskirts Press. ISBN 978-1-4787-0462-1.

- Eastburn, Kathryn (2008) A Sacred Feast: Reflections on Sacred Harp Singing and Dinner on the Ground University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1831-4

- Jackson, George Pullen (1933a) White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-486-21425-7

- Jackson, George Pullen (1933b) "Buckwheat notes", The Musical Quarterly XIX(4):393–400.

- Miller, Kiri (ed.) (2002) The Chattahoochee Musical Convention, 1852–2002: A Sacred Harp Historical Sourcebook. The Sacred Harp Museum. ISBN 1-887617-13-2

- Miller, Kiri (2007) Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-03214-4

- Sommers, Laurie Kay (2010) "Hoboken Style: Meaning and Change in Okefenokee Sacred Harp Singing" Southern Spaces ISSN 1551-2754

- Steel, David Warren with Richard H. Hulan (2010) The Makers of the Sacred Harp. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07760-9

- Wallace, James B. (2007) "Stormy Banks and Sweet Rivers: A Sacred Harp Geography" Southern Spaces ISSN 1551-2754

External links[editar]

- Fasola Home Page, a web site dedicated to Sacred Harp music

- Sacred Harp Singing by Warren Steel, another web site on the Sacred Harp

- Sacred Harp and Related Shape-Note Music Resources, a large and well-annotated collection of resources on shape-note music

- Sacred Harp Publishing Company, songbooks and other resources

- Public-domain editions: The Sacred Harp (1860), (1911, rev. J. S. James et al.) (for other shape note tunebooks see these links)

- «Wiregrass Sacred Harp Singers Era 1980». Musics of Alabama: A Compilation. Alabama Center for Traditional Culture. Archivado desde el original el 8 January 2013. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - The Sacred Harp, article from the New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Florida Memory: Sacred Harp, includes an educational unit on Sacred Harp

- Sacred Harp Music, article on Sacred Harp from the Handbook of Texas online

- Sacred Harp singing in Texas, includes composer sketches, including one of B. F. White

- Shape Note Historical Background

- Stormy Banks and Sweet Rivers: A Sacred Harp Geography

- Sacred Harp Singing historical marker

Online media[editar]

- Sweet is the Day, streaming documentary on the Wootten family of Sand Mountain, Alabama

- John Quincy Wolf Collection: Sacred Harp includes recordings of Sacred Harp singings

- BostonSing, a large collection of shape-note recordings

- BBC Radio 4 programme about Sacred Harp music

[[Category:Sacred Harp| ]] [[Category:American styles of music]] [[Category:American Christian hymns]] [[Category:Christian music genres]] [[Category:Musical notation]] [[Category:Shape note]] [[Category:Four-part harmony]]