Usuario:Michael junior obregon pozo/Taller/Relaciones a través del estrecho de Taiwán

| Michael junior obregon pozo/Taller/Relaciones a través del estrecho de Taiwán | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Izquierda: Bandera de la República de China; derecha: Bandera de la República Popular China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nombre chino | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tradicional | 海峽兩岸關係 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplificado | 海峡两岸关系 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

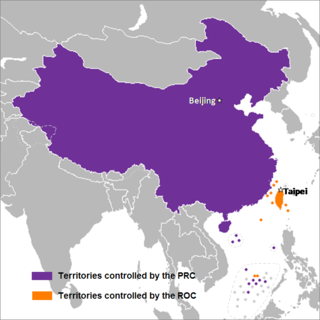

Relaciones a través del Estrecho (a veces llamadas relaciones entre el continente y Taiwán[1] o relaciones Taiwán-China[2]) se refieren a la relación entre las siguientes dos entidades políticas, que están separadas por el Estrecho de Taiwán en el Océano Pacífico occidental:

- la República Popular China (RPC), comúnmente conocida como "China"

- la República de China (ROC), comúnmente conocida como "Taiwán"

La relación ha sido compleja y controvertida debido a la disputa sobre el estatus político de Taiwán después de que la administración de Taiwán fuera transferida de Japón al final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en 1945 y la posterior división de China en los dos antes mencionados en 1949 como resultado de la guerra civil, y depende de dos cuestiones clave: si las dos entidades son dos países separados (ya sea como "Taiwán" y "China" o Dos Chinas: "República de China" y "República Popular de China") o dos "regiones "o partes del mismo país (es decir," Una China ") con gobiernos rivales. La expresión "Relaciones a través del Estrecho" se considera un término neutral que evita la referencia al estatus político de cualquiera de las partes.

Al final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en 1945, la administración de Taiwán fue transferida a la República de China (ROC) desde el Imperio de Japón, aunque siguen existiendo cuestiones legales con respecto al lenguaje del Tratado de San Francisco. En 1949, con la Guerra Civil China girando decisivamente a favor del Partido Comunista de China (PCCh), el gobierno de la República de China liderado por el Kuomintang (KMT) se retiró a Taiwán y estableció la capital provisional en Taipei, mientras que el PCCh proclamó el Gobierno de la República Popular China (PRC) en Beijing. Nunca se ha firmado ningún tratado de armisticio o de paz y continúa el debate sobre si la guerra civil ha terminado legalmente.[3]

Desde entonces, las relaciones entre los gobiernos de Beijing y Taipei se han caracterizado por contactos limitados, tensiones e inestabilidad. En los primeros años, continuaron los conflictos militares, mientras que diplomáticamente ambos gobiernos competían por ser el "gobierno legítimo de China". Desde la democratización de Taiwán, la cuestión del estatus político y legal de Taiwán ha cambiado de enfoque hacia la elección entre la unificación política con China continental o la independencia de jure de Taiwán. La República Popular China sigue siendo hostil a cualquier declaración formal de independencia y mantiene su reclamo sobre Taiwán.

Al mismo tiempo, han aumentado los intercambios no gubernamentales y semigubernamentales entre las dos partes. A partir de 2008, comenzaron las negociaciones para restaurar los Tres Enlaces (postal, transporte, comercio) entre las dos partes, interrumpidos desde 1949. El contacto diplomático entre las dos partes se ha limitado generalmente a las administraciones del Kuomintang en Taiwán. Sin embargo, durante las administraciones del Partido Democrático Progresista, las negociaciones continúan ocurriendo sobre asuntos prácticos a través de canales informales.[4]

Comparison of the two states[editar]

Historia[editar]

Cronología[editar]

Antes de 1949[editar]

La historia temprana de las relaciones a través del Estrecho involucra el intercambio de culturas, personas y tecnología.[20][21][22] Sin embargo, ninguna dinastía china incorporó formalmente a Taiwán en la antigüedad.[23] En los siglos XVI y XVII, Taiwán llamó la atención de los primeros exploradores portugueses, luego holandeses y españoles. En 1624, los holandeses establecieron su primer asentamiento en Taiwán. En 1662, Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong), un leal a la dinastía Ming, derrotó a los gobernantes holandeses de Taiwán y tomó la isla, estableciendo el primer régimen formalmente chino Han en Taiwán. Los herederos de Koxinga utilizaron Taiwán como base para lanzar incursiones en China continental contra la dinastía manchú Qing. Sin embargo, fueron derrotados en 1683 por las fuerzas Qing. Al año siguiente, Taiwán se incorporó a la provincia de Fujian. Durante los dos siglos siguientes, el gobierno imperial prestó poca atención a Taiwán.

La situación cambió en el siglo XIX, con otras potencias mirando cada vez más a Taiwán por su ubicación estratégica y sus recursos. En respuesta, la administración comenzó a implementar una campaña de modernización. En 1887, la provincia de Fujian-Taiwán fue declarada por decreto imperial. En 10 años, Taiwán se había convertido en una de las provincias más modernas del Imperio. Sin embargo, la caída de Qing dejo atrás el desarrollo de Taiwán, y en 1895, tras su derrota en la Primera Guerra Sino-Japonesa, el gobierno imperial cedió Taiwán a Japón a perpetuidad. Los leales Qing resistieron brevemente el dominio japonés bajo la bandera de la "República de Taiwán", pero fueron rápidamente rechazados por las autoridades japonesas.[24]

Japón gobernó Taiwán hasta 1945. Durante este tiempo, Taiwán, como parte del Imperio japonés, fue una jurisdicción extranjera en relación primero con el Imperio Qing y, después de 1912, con la República de China. En 1945, Japón fue derrotado en la Segunda Guerra Mundial y entregó sus fuerzas en Taiwán a los Aliados, con la República de China, luego gobernada por el Kuomintang (KMT), tomando la custodia de la isla. El período de gobierno del Kuomintang de la posguerra sobre China (1945-1949) estuvo marcado en Taiwán por el conflicto entre los residentes locales y la nueva autoridad del KMT. Los taiwaneses se rebelaron contra el 28 de febrero de 1947 en el incidente del 28 de febrero, que fue reprimido violentamente por el KMT. En esta época se sembraron las semillas del movimiento independentista de Taiwán.

China pronto se vio envuelta en una guerra civil a gran escala. En 1949, la guerra se volvió decisivamente contra el KMT y a favor del PCCh. El 1 de octubre de 1949, el PCCh bajo la presidencia de Mao Zedong proclamó la fundación de la República Popular China en Beijing. El gobierno capitalista de la República de China se retiró a Taiwán, y finalmente declaró a Taipei su capital temporal en diciembre de 1949.[25]

Del estancamiento militar a la guerra diplomática (1949-1979)[editar]

Los dos gobiernos continuaron en estado de guerra hasta 1979. En octubre de 1949, el intento de la República Popular China de tomar la isla de Kinmen controlada por la República de China se vio frustrado en la Batalla de Kuningtou, deteniendo el avance del EPL hacia Taiwán.[26] Las otras operaciones anfibias de los comunistas de 1950 tuvieron más éxito: llevaron a la conquista comunista de la isla de Hainan en abril de 1950, la captura de las islas Wanshan frente a la costa de Guangdong (mayo-agosto de 1950) y de la isla de Zhoushan frente a Zhejiang (mayo de 1950).[27]

En junio de 1949, la República de China declaró un "cierre" de todos los puertos chinos y su armada intentó interceptar todos los barcos extranjeros. El cierre cubrió desde un punto al norte de la desembocadura del río Min en la provincia de Fujian hasta la desembocadura del río Liao en Manchuria.[28] Dado que la red ferroviaria de China estaba subdesarrollada, el comercio norte-sur dependía en gran medida de las rutas marítimas. La actividad naval de la República de China también causó graves dificultades a los pescadores chinos.

Después de perder China, un grupo de aproximadamente 12.000 soldados del KMT escapó a Birmania y continuó lanzando ataques de guerrilla en el sur de China. Su líder, el general Li Mi, recibió un salario del gobierno de la República de China y se le otorgó el título nominal de gobernador de Yunnan. Inicialmente, Estados Unidos apoyó estos remanentes y la Agencia Central de Inteligencia les brindó ayuda. Después de que el gobierno birmano apeló a las Naciones Unidas en 1953, Estados Unidos comenzó a presionar a la República de China para que retirara a sus leales. A fines de 1954, casi 6.000 soldados habían abandonado Birmania y Li Mi declaró que su ejército se disolvió. Sin embargo, quedaron miles, y la República de China continuó suministrándolos y comandándolos, incluso suministrando refuerzos en secreto a veces.

La insurgencia islámica del Kuomintang en China (1950-1958) fue combatida por oficiales del ejército musulmán del Kuomintang que se negaron a rendirse a los comunistas durante las décadas de 1950 y 1960.

Durante la Guerra de Corea, algunos soldados chinos comunistas capturados, muchos de los cuales eran originalmente soldados del KMT, fueron repatriados a Taiwán en lugar de a China. Una fuerza guerrillera del KMT continuó realizando incursiones transfronterizas en el suroeste de China a principios de la década de 1950. El gobierno de la República de China lanzó una serie de bombardeos aéreos en ciudades costeras clave de China, como Shanghai.

Aunque los Estados Unidos lo consideraban una responsabilidad militar, la República de China consideró que las islas restantes en Fujian eran vitales para cualquier campaña futura para derrotar a la República Popular China y retomar China. El 3 de septiembre de 1954, comenzó la primera crisis del estrecho de Taiwán cuando el EPL comenzó a bombardear Quemoy y amenazó con tomar las islas Dachen.[28] El 20 de enero de 1955, el EPL tomó la cercana isla de Yijiangshan, con toda la guarnición de la República de China de 720 soldados muertos o heridos defendiendo la isla. El 24 de enero del mismo año, el Congreso de los Estados Unidos aprobó la Resolución de Formosa que autoriza al presidente a defender las islas costeras de la República de China.[28] La Primera crisis del Estrecho de Taiwán terminó en marzo de 1955 cuando el EPL cesó su bombardeo. La crisis llegó a su fin durante la conferencia de Bandung.[28]

La Segunda Crisis del Estrecho de Taiwán comenzó el 23 de agosto de 1958 con enfrentamientos aéreos y navales entre la República Popular China y las fuerzas militares de la República de China, lo que llevó a un intenso bombardeo de artillería de Quemoy (por la República Popular China) y Amoy (por la República de China), y terminó en noviembre del mismo año.[28] Los barcos patrulleros del EPL bloquearon las islas de los barcos de suministro de la República de China. Aunque Estados Unidos rechazó la propuesta de Chiang Kai-shek de bombardear baterías de artillería chinas, rápidamente se movió para suministrar aviones de combate y misiles antiaéreos a la República de China. También proporcionó buques de asalto anfibios al suministro terrestre, ya que un buque naval de la República de China hundido estaba bloqueando el puerto. El 7 de septiembre, Estados Unidos escoltó un convoy de barcos de suministro de la República de China y la República Popular China se abstuvo de disparar. El 25 de octubre, la República Popular China anunció un "alto el fuego de días pares": el EPL solo bombardearía a Quemoy en los días impares.

A pesar del final de las hostilidades, las dos partes nunca han firmado ningún acuerdo o tratado para poner fin oficialmente a la guerra.

Después de la década de 1950, la "guerra" se volvió más simbólica que real, representada por bombardeos de artillería de encendido y apagado hacia y desde Kinmen. En años posteriores, los proyectiles vivos fueron reemplazados por hojas de propaganda. El bombardeo cesó finalmente en 1979 tras el establecimiento de relaciones diplomáticas entre la República Popular China y Estados Unidos.

Durante este período, el movimiento de personas y mercancías prácticamente cesó entre los territorios controlados por la República Popular China y la República de China. Hubo desertores ocasionales. Un desertor de alto perfil fue Justin Yifu Lin, quien nadó a través del estrecho de Kinmen hasta China y fue Jefe de economía y vicepresidente senior del Banco Mundial de 2008 a 2012.

La mayoría de los observadores esperaban que el gobierno de Chiang cayera eventualmente en respuesta a una invasión comunista de Taiwán, y Estados Unidos inicialmente no mostró interés en apoyar al gobierno de Chiang en su posición final. Las cosas cambiaron radicalmente con el inicio de la Guerra de Corea en junio de 1950. En este punto, permitir una victoria comunista total sobre Chiang se volvió políticamente imposible en los Estados Unidos, y el presidente Harry S. Truman ordenó que la Séptima Flota de los Estados Unidos en el estrecho de Taiwán evitara que la República de China y la República Popular China se ataquen entre sí.[29]

Después de que la República de China se quejara ante las Naciones Unidas contra la Unión Soviética que apoyaba a la República Popular China, la Resolución 505 de la Asamblea General de la ONU fue adoptada el 1 de febrero de 1952 para condenar a la Unión Soviética.

Diplomáticamente durante este período, hasta alrededor de 1971, el gobierno de la República de China continuó siendo reconocido como el gobierno legítimo de China y Taiwán por la mayoría de los gobiernos de la OTAN. El gobierno de la República Popular China fue reconocido por los países del bloque soviético, miembros del movimiento no alineado y algunas naciones occidentales como el Reino Unido y los Países Bajos. Ambos gobiernos afirmaron ser el gobierno legítimo de China y etiquetaron al otro como ilegítimo. La propaganda de la guerra civil impregnó el plan de estudios de educación. Cada lado retrató a la gente del otro viviendo en una miseria infernal. En los medios oficiales, cada bando llamó a los otros "bandidos". La República de China también reprimió las expresiones de apoyo a la identidad taiwanesa o la independencia de Taiwán.

Tanto la República de China como la República Popular China participaron en guerras por poderes en otros países para ganar influencia y aliados. Tendrían fuerzas de poder o proporcionarían ayuda o apoyo militar durante el conflicto, para apoyar sus intereses. Algunos conflictos notables incluyen: conflicto interno en Myanmar, guerra de Corea, guerra civil de Laos, disturbios de Hong Kong en 1956, insurgencia comunista en Tailandia, incidente del 12-3, disturbios de izquierda en Hong Kong de 1967 y rebelión del NDF

Deshielo de las relaciones (1979-1998)[editar]

Tras la ruptura de las relaciones oficiales entre los Estados Unidos y la República de China en 1979, el gobierno de la República de China bajo Chiang Ching-kuo mantuvo una política de "Tres Noes" en lo que respecta a la comunicación con el gobierno chino. Sin embargo, esta política se revisó tras el secuestro de un avión de carga de China Airlines en mayo de 1986, en el que el piloto taiwanés sometió a otros miembros de la tripulación y voló el avión a Guangzhou. En respuesta, Chiang envió delegados a Hong Kong para discutir con los funcionarios de la República Popular China el regreso del avión y la tripulación, lo que se considera un punto de inflexión entre las relaciones a través del Estrecho.

En 1987, el gobierno de la República de China comenzó a permitir visitas a China. Esto benefició a muchos, especialmente a los viejos soldados del KMT, que habían estado separados de su familia en China durante décadas. Esto también resultó ser un catalizador para el deshielo de las relaciones entre las dos partes. Los problemas generados por un mayor contacto exigieron un mecanismo de negociaciones regulares.

En 1988, la República Popular China aprobó una directriz, un reglamento de 22 puntos, para fomentar las inversiones de la República de China en la República Popular China. Garantizaba que los establecimientos de la República de China no serían nacionalizados, y que las exportaciones estaban libres de aranceles, a los empresarios de la República de China se les otorgarían múltiples visas para facilitar el movimiento.

Para negociar con China sobre cuestiones operativas sin comprometer la posición del gobierno de negar la legitimidad de la otra parte, el gobierno de la República de China bajo Chiang Ching-kuo creó la "Fundacion de Intercambio a travéz del Estrecho" (SEF), una institución nominalmente no gubernamental dirigida directamente por el Consejo de Asuntos del Continente de la República de China, un instrumento del Yuan Ejecutivo. La República Popular China respondió a esta iniciativa con la creación de la Asociación para las Relaciones a Través del Estrecho de Taiwán (ARATS), dirigida directamente por la Oficina de Asuntos de Taiwán del Consejo de Estado. Este sistema, descrito como "guantes blancos", permitió a los dos gobiernos interactuar entre sí de forma semioficial sin comprometer sus respectivas políticas de soberanía.

Las dos organizaciones, encabezadas por los más respetados estadistas Koo Chen-fu y Wang Daohan, iniciaron una serie de conversaciones que culminaron en las reuniones de 1992, que, junto con la correspondencia posterior, pueden haber establecido el Consenso de 1992, en virtud del cual ambas partes acordaron deliberar. ambigüedad en cuestiones de soberanía, a fin de abordar cuestiones operativas que afecten a ambas partes.

También durante este tiempo, sin embargo, la retórica del presidente de la República de China, Lee Tung-hui, comenzó a inclinarse aún más hacia la independencia de Taiwán. Antes de la década de 1990, la República de China había sido un estado autoritario de partido único comprometido con una eventual unificación con China. Sin embargo, con las reformas democráticas, las actitudes del público en general comenzaron a influir en la política de Taiwán. Como resultado, el gobierno de la República de China se alejó de su compromiso con la política de una sola China y adoptó una identidad política separada para Taiwán. El Ejército Popular de Liberación intentó influir en las elecciones de la República de China de 1996 en Taiwán mediante la realización de un ejercicio de misiles diseñado para advertir a la Coalición Pan-Verde a favor de la independencia, lo que condujo a la Tercera Crisis del Estrecho de Taiwán. En 1998, las conversaciones semioficiales se habían interrumpido.

Fin del contacto hostil (1998-2008)[editar]

Chen Shui-bian, del Partido Progresista Democrático independentista, fue elegido presidente de la República de China en 2000. En su discurso inaugural, Chen Shui-bian se comprometió con los Cuatro Noes y el Uno Sin, en particular, prometiendo no buscar ni la independencia ni la unificación además de rechazar el concepto de relaciones especiales de estado a estado expresado por su predecesor, Lee Teng-hui, así como establecer los Tres Mini-Enlaces. Además, siguió una política de normalización de las relaciones económicas con la República Popular China.[30] Expresó cierta disposición a aceptar el Consenso de 1992, una condición previa establecida por la República Popular China para el diálogo, pero se echó atrás después de una reacción violenta dentro de su propio partido.[31] La República Popular China no involucró a la administración de Chen, pero mientras tanto, en 2001, Chen levantó la prohibición de 50 años sobre el comercio directo y la inversión con la República Popular China, lo que hizo posible la posterior ECFA.[32] En noviembre de 2001, Chen repudió "una sola China" y pidió conversaciones sin condiciones previas.[33]

Hu Jintao se convirtió en secretario general del Partido Comunista de China a fines de 2002, sucediendo a Jiang Zemin como líder supremo de facto de China. Hu continuó insistiendo en que las conversaciones solo pueden llevarse a cabo bajo un acuerdo del principio de "una sola China". Al mismo tiempo, Hu y la República Popular China continuaron con la acumulación de misiles militares a través del estrecho de Taiwán mientras amenazaban con una acción militar contra Taiwán en caso de que declarara su independencia o si la República Popular China considera que todas las posibilidades de una unificación pacífica están completamente agotadas. La República Popular China también continuó aplicando presión diplomática a otras naciones para aislar diplomáticamente a la República de China. Sin embargo, durante la guerra de Irak de 2003, la República Popular China permitió que las aerolíneas taiwanesas usaran el espacio aéreo de China.[34]

Después de la reelección de Chen Shui-bian en 2004, el gobierno de Hu cambió la política general de no contacto anterior, un vestigio de la administración de Jiang Zemin. Bajo la nueva política, por un lado, el gobierno de la República Popular China continuó con una política de no contacto hacia Chen Shui-bian. Mantuvo su preparación militar contra Taiwán y siguió una política vigorosa de aislar diplomáticamente a Taiwán. En marzo de 2005, el Congreso Nacional del Pueblo aprobó la Ley Antisecesión, que formaliza los "medios no pacíficos" como opción de respuesta a una declaración formal de independencia en Taiwán.

Por otro lado, la administración de la República Popular China relajó su retórica en relación con Taiwán y buscó el contacto con grupos apolíticos o políticamente no independentistas en Taiwán. En su declaración del 17 de mayo de 2004, Hu Jintao hizo propuestas amistosas a Taiwán para reanudar las negociaciones para los "tres enlaces", reducir los malentendidos y aumentar las consultas. En la Ley Antisecesión aprobada en 2005, el gobierno de la República Popular China se comprometió por primera vez con autoridad a negociar sobre la base de la igualdad de condiciones entre las dos partes y se abstuvo de imponer la política de "una China" como condición previa para las conversaciones. El PCCh aumentó los contactos de partido a partido con el KMT, entonces el partido de oposición en Taiwán. A pesar de haber sido las partes en guerra en la Guerra Civil China, el PCCh y el KMT también tienen una historia de cooperación, cuando las dos partes cooperaron dos veces en la Expedición del Norte y la guerra contra Japón; Además, ambas partes, por diversas razones históricas e ideológicas, se adhieren a sus respectivas versiones de la política de una sola China.

Reanudación del contacto de alto nivel (2008-2016)[editar]

El aumento de los contactos culminó en las visitas de la colición Pan-Azul de 2005 a China, incluida una reunión entre Hu y el entonces presidente del KMT, Lien Chan, en abril de 2005.[35][36] El 22 de marzo de 2008, Ma Ying-jeou del KMT ganó las elecciones presidenciales en Taiwán. También ganó una amplia mayoría en la Legislatura.[37]

Ha seguido una serie de reuniones entre las dos partes. El 12 de abril de 2008, Hu Jintao mantuvo una reunión con el entonces vicepresidente electo de la República de China, Vincent Siew, como presidente de la Fundación del Mercado Común del Estrecho durante el Foro de Boao para Asia. El 28 de mayo de 2008, Hu se reunió con el ex presidente del KMT, Wu Po-hsiung, la primera reunión entre los jefes del PCCh y el KMT como partidos gobernantes. Durante esta reunión, Hu y Wu acordaron que ambas partes deberían reiniciar el diálogo semioficial bajo el consenso de 1992. Wu comprometió el KMT contra la independencia de Taiwán, pero también enfatizó que una "identidad de Taiwán" no equivale a "independencia de Taiwán". Hu comprometió a su gobierno a abordar las preocupaciones del pueblo taiwanés con respecto a la seguridad, la dignidad y el "espacio vital internacional", dando prioridad a discutir el deseo de Taiwán de participar en la Organización Mundial de la Salud.

Tanto Hu como su nueva contraparte, Ma Ying-jeou, están de acuerdo en que el Consenso de 1992 es la base para las negociaciones entre los dos lados del estrecho de Taiwán. El 26 de marzo de 2008, Hu Jintao sostuvo una conversación telefónica con el presidente estadounidense George W. Bush, en la que explicó que el "Consenso de 1992" considera que "ambas partes reconocen que hay una sola China, pero están de acuerdo en diferir en su definición".[38] La primera prioridad para la reunión SEF-ARATS será la apertura de los tres enlaces, especialmente los vuelos directos entre China y Taiwán.

Estos eventos sugieren una política de las dos partes que se basa en la ambigüedad deliberada del Consenso de 1992 para evitar las dificultades que surgen al afirmar la soberanía. Como dijo Wu Po-hsiung durante una conferencia de prensa en su visita a China en 2008, "no nos referimos a la 'República de China' mientras la otra parte no se refiera a la 'República Popular de China'". Desde las elecciones de marzo en Taiwán, el gobierno de la República Popular China no ha mencionado la "política de una sola China" en ningún anuncio oficial. La única excepción ha sido una breve aberración en un comunicado de prensa del Ministerio de Comercio, que describió que Vincent Siew estaba de acuerdo con el "consenso de 1992 y la" política de una sola China ". Tras una protesta inmediata de Siew, la parte de la República Popular China se retractó de la prensa y emitió declaraciones de disculpa enfatizando que solo los comunicados de prensa publicados por la Agencia de Noticias Xinhua representaban la posición oficial de la República Popular China. El comunicado de prensa oficial sobre este evento no mencionó la Política de Una China.[39]

El ex presidente de la República de China, Ma Ying-jeou, ha abogado por que las relaciones a través del Estrecho deben pasar del "no reconocimiento mutuo" a la "no negación mutua".[40]

El diálogo a través de organizaciones semioficiales (la SEF y la ARATS) se reabrió el 12 de junio de 2008 sobre la base del Consenso de 1992, con la primera reunión celebrada en Beijing. Ni la República Popular China ni la República de China reconocen a la otra parte como una entidad legítima, por lo que el diálogo se realizó en nombre de los contactos entre la SEF y la ARATS en lugar de los dos gobiernos, aunque la mayoría de los participantes eran en realidad funcionarios de los gobiernos de la República Popular China o la República de China. Chen Yunlin, presidente de la ARATS, y Chiang Pin-kung, presidente de la SEF, firmaron archivos el 13 de junio, acordando que los vuelos directos entre las dos partes comenzarían el 4 de julio[41] y que Taiwán permitiría la entrada de hasta 3000 visitantes de China todos los días.[42]

The financial relationship between the two areas improved on 1 May 2009 in a move described as "a major milestone" by The Times.[43] The ROC's financial regulator, the Financial Supervisory Commission, announced that Chinese investors would be permitted to invest in Taiwan's money markets for the first time since 1949.[43] Investors can now apply to purchase Taiwan shares that do not exceed one tenth of the value of the firm's total shares.[43] The move came as part of a “step by step” movement which is supposed to relax restrictions on Chinese investment. Taipei economist Liang Chi-yuan, commented: “Taiwan's risk factor as a flash point has dropped significantly with its improved ties with Chinese. The Chinese would be hesitant about launching a war as their investment increases here.”[43] China's biggest telecoms carrier, China Mobile, was the first company to avail of the new movement by spending $529 million on buying 12 percent of Far EasTone, the third largest telecoms operator in Taiwan.[43]

President Ma has called repeatedly for the PRC to dismantle the missile batteries targeted on Taiwan's cities, without result.[44]

On 30 January 2010, the Obama administration announced it intended to sell $6.4 billion worth of antimissile systems, helicopters and other military hardware to Taiwan, an expected move which was met with reaction from Beijing: in retaliation, China cut off all military-to-military ties with Washington and warned that US-China cooperation on international issues could suffer as a result of the sales.[45]

A report from Taiwan's Ministry of National Defense said that China's current charm offensive is only accommodating on issues that do not undermine China's claim to Taiwan and that the PRC would invade if Taiwan declared independence, developed weapons of mass destruction, or suffered from civil chaos.[46]

On the 100th anniversary of the Republic of China (Xinhai Revolution), President Ma called on the PRC to embrace Sun Yat-sen's call for freedom and democracy.[47]

In June 2013, China offered 31 new measures to better integrate Taiwan economically.[48]

In October 2013, in a hotel lobby on the sidelines of the APEC Indonesia 2013 meetings in the Indonesian island of Bali, Wang Yu-chi, Minister of the Mainland Affairs Council, spoke briefly with Zhang Zhijun, Minister of the Taiwan Affairs Office, each addressing the other by his official title. Both called for the establishment of a regular dialogue mechanism between their two agencies to facilitate cross-strait engagement. Zhang also invited Wang to visit China.[49][50]

On 11 February 2014, Wang met with Zhang in Nanjing, in the first official, high-level, government-to-government contact between the two sides since 1949. The meeting took place at Purple Palace Nanjing.[51][52] Nanjing was the capital of the Republic of China during the period in which it actually ruled China.[53][54] During the meeting, Wang and Zhang agreed on establishing a direct and regular communication channel between the two sides for future engagement under the 1992 Consensus. They also agreed on finding a solution for health insurance coverage for Taiwanese students studying in Mainland China, on pragmatically establishing SEF and ARATS offices in their respective territories and on studying the feasibility of allowing visits to detained persons once these offices have been established. Before shaking hands, Wang addressed Zhang as "TAO Director Zhang Zhijun" and Zhang addressed Wang as "Minister Wang Yu-chi" without mentioning the name Mainland Affairs Council.[55] However, China's Xinhua News Agency referred to Wang as the "Responsible Official of Taiwan's Mainland Affairs Council" (en chino simplificado, 台湾方面大陆委员会负责人; pinyin, Táiwān Fāngmiàn Dàlù Wěiyuánhuì Fùzérén)[56] in its Chinese-language news and as "Taiwan's Mainland Affairs Chief" in its English-language news.[57] On 25–28 June 2014, Zhang paid a retrospective visit to Taiwan, making him the highest CCP official to ever visit Taiwan.

In September 2014, Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party to adopt a more uncompromising stance than his predecessors as he called for the "one country, two systems" model to be applied to Taiwan. In Taiwan it was noted that Beijing was no longer referring to the 1992 Consensus.[58]

On 7 November 2015, Xi and Ma met and shook hands in Singapore, marking the first ever meeting between leaders of both sides since the end of Chinese Civil War in 1949. They met within their capacity as Leader of Mainland China and Leader of Taiwan respectively.

On 30 December 2015, a hotline connecting the head of the Mainland Affairs Council and the head of the Taiwan Affairs Office was established.[59] First conversation via the hotline between the two heads was made on 5 February 2016.[60]

In March 2016, former ROC Justice Minister Luo Ying-shay embarked on a 5-day historic visit to Mainland China, making her the first Minister of the Government of the Republic of China to visit Mainland China after the end of Chinese Civil War in 1949.[61]

Deteriorating relations (2016–present)[editar]

In the 2016 Taiwan general elections, Tsai Ing-wen and the DPP captured landslide victories.[62] Beijing has expressed its dissatisfaction with Tsai's refusal to accept the "1992 Consensus".[63]

On 1 June 2016, it was confirmed that former President Ma Ying-jeou would visit Hong Kong on 15 June to attend and deliver speech on Cross-Strait relations and East Asia at the 2016 Award for Editorial Excellence dinner at Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre.[64] The Tsai Ing-wen administration blocked Ma from traveling to Hong Kong,[65] and he gave prepared remarks via teleconference instead.[66]

In September 2016, eight magistrates and mayors from Taiwan visited Beijing, which were Hsu Yao-chang (Magistrate of Miaoli County), Chiu Ching-chun (Magistrate of Hsinchu County), Liu Cheng-ying (Magistrate of Lienchiang County), Yeh Hui-ching (Deputy Mayor of New Taipei City), Chen Chin-hu (Deputy Magistrate of Taitung County), Lin Ming-chen (Magistrate of Nantou County), Fu Kun-chi (Magistrate of Hualien County) and Wu Cheng-tien (Deputy Magistrate of Kinmen County). Their visit was aimed to reset and restart cross-strait relations after President Tsai Ing-wen took office on 20 May 2016. The eight local leaders reiterated their support of One-China policy under the 1992 consensus. They met with Taiwan Affairs Office Head Zhang Zhijun and Chairperson of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference Yu Zhengsheng.[67][68][69]

In November 2016, First Lady Peng Liyuan's brother Peng Lei (彭磊) visited Chiayi City from Mainland China to attend the funeral of their uncle Lee Hsin-kai (李新凱), a veteran KMT member. The funeral was kept low key and was attended by KMT Chairperson Hung Hsiu-chu, KMT Vice Chairperson Huang Min-hui and other government and party officials.[70][71]

In October 2017, Tsai Ing-wen expressed hopes that both sides would restart their cross-strait relations after the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, and argued that new practices and guidelines governing mutual interaction should be examined.[72] Regarding the old practices, Tsai stated that “If we keep sticking to these past practices and ways of thinking, it will probably be very hard for us to deal with the volatile regional situations in Asia”.[73] Relations with the Mainland had stalled since Tsai took office in 2016.[74]

In his opening speech at the 19th Communist Party Congress, CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping emphasized the PRC's sovereignty over Taiwan, stating that “We have sufficient abilities to thwart any form of Taiwan independence attempts."[75] At the same time, he offered the chance for open talks and "unobstructed exchanges" with Taiwan as long as the government moved to accept the 1992 consensus.[75][76] His speech received a tepid response from Taiwanese observers, who argued that it did not signal any significant changes in Beijing's Taiwan policy, and showed "no significant goodwill, nor major malice."[77][78]

Beijing has recently significantly restricted the number of Chinese tour groups allowed to visit Taiwan to place pressure upon President Tsai Ing-wen. Apart from Taiwan, the Holy See and Palau have also been pressured to recognize the PRC over the ROC.[79]

In April 2018, political parties and organizations demanding a referendum on Taiwan's independence have formed an alliance to further their initiative. The Formosa Alliance was established, prompted by a sense of crisis in the face of growing pressure from China for unification. The alliance wants to hold a referendum on Taiwan's independence in April 2019, change the island's name from the Republic of China to Taiwan, and apply for membership in the United Nations.[80] In May 2018, China engaged in military exercises around Taiwan to pressure Taiwan not to become independent.[81]

In 2018 The Diplomat reported that China conducts hybrid warfare against Taiwan.[82] Taiwan's leaders, including President Tsai and Premier William Lai, and the international press have repeatedly accused China of spreading fake news via social media to create divisions in Taiwanese society, influence voters and support candidates more sympathetic to Beijing ahead of the 2018 Taiwanese local elections.[83][84][85][86] Researchers say the PRC government is allowing misinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic to flow into Taiwan.[87]

In January 2020 Tsai Ing-wen said that Taiwan is already an independent country called the Republic of China (Taiwan), and Beijing must face this reality.[88] According to Reuters, around 2020 the Taiwanese public turned further against mainland China, due to fallout from the Hong Kong protests and also due to China's continued determination to keep Taiwan out of the World Health Organization despite the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The opposition KMT also appeared to distance itself from China in 2020, stating it would review its unpopular advocacy of closer ties with China.[89] In March 2021, KMT chairman Johnny Chiang rejected the "one country, two systems" as a feasible model for Taiwan, citing Beijing's response to protests in Hong Kong as well as the value that Taiwanese place in political freedoms.[90]

In 2021, multiple Chinese military planes entered Taiwan's ADIZ.[91][92][93][94]The Hong Kong Economic, Trade and Cultural Office in Taiwan suspended its operation indefinitely on 18 May 2021 followed by Macau Office starting 19 June 2021.[95]

In July 2021 Taiwan’s presidential office extended condolences and sympathy to those effected by historic flooding in Zhengzhou, China. In addition Taiwanese companies and individuals made donations of money and supplies to help those effected.[96] China indirectly thanked President Tsai for expressing concern as well as offering thanks to companies and individuals who made contributions to the relief effort.[97]

Semi-official relations[editar]

Interpretation of the relations by sitting leaders[editar]

Presidents Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo have steadily maintained that there is only one China, the sole representative of which was the ROC, and that the PRC government was illegitimate, while PRC leaders have maintained the converse that the PRC was the sole representative of China. In 1979, Deng Xiaoping proposed a model for the incorporation of Taiwan into the People's Republic of China which involved a high degree of autonomy within the Chinese state, similar to the model proposed to Hong Kong which would eventually become one country, two systems. On 26 June 1983, Deng proposed a meeting between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party as equal political parties and on 22 February, he officially proposed the one country, two systems model. In September 1990, under the presidency of Lee Teng-hui, the National Unification Council was established in Taiwan and in January 1991, the Mainland Affairs Council was established; in March 1991, the "Guidelines for National Unification" were adopted and on 30 April 1991, the period of mobilization for the suppression of Communist rebellion was terminated. Thereafter, the two sides conducted several rounds of negotiations through the informal Straits Exchange Foundation and Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits.[98]

On 22 May 1995, the United States granted Lee Teng-hui a visit to his alma mater, Cornell University, which resulted in the suspension of cross-strait exchanges by China, as well as the subsequent Third Taiwan Strait Crisis. Lee was labelled as a "traitor" attempting to "split China" by the PRC.[99][100] In an interview on 9 July 1999, President Lee Teng-hui defined the relations between Taiwan and mainland China as "between two countries (國家), at least special relations between two countries," and that there was no need for the Republic of China to declare independence since it had been independent since 1912 (the founding date of the Republic of China), thereby identifying the Taiwanese state with the Republic of China. Later, the MAC published an English translation of Lee's remarks referring instead to "two states of one nation," later changed on 22 July to "special state-to-state relations." In response, China denounced the theory and demanded retractions. Lee began to backpedal from his earlier marks, emphasizing the 1992 consensus, whereby representatives from the two sides agreed that there was only one China, of which Taiwan was a part. However, the ROC maintained that the two sides agreed to disagree about which government represented China, whereas the PRC maintains that the two sides agreed that the PRC was the sole representative of China.[101]

On August 3, 2002, president Chen Shui-bian defined the relationship as One Country on Each Side. The PRC subsequently cut off official contact with the ROC government.[102]

The ROC position under President Ma Ying-jeou backpedaled to a weaker version of Lee Teng-hui's position. On 2 September 2008, former ROC President Ma Ying-jeou was interviewed by the Mexico-based newspaper El Sol de México and he was asked about his views on the subject of 'two Chinas' and if there is a solution for the sovereignty issues between the two. Ma replied that the relations are neither between two Chinas nor two states. It is a special relationship. Further, he stated that the sovereignty issues between the two cannot be resolved at present, but he quoted the '1992 Consensus' as a temporary measure until a solution becomes available.[103] Former spokesman for the ROC Presidential Office Wang Yu-chi later elaborated the President's statement and said that the relations are between two regions of one country, based on the ROC Constitutional position, the Statute Governing the Relations Between the Peoples of the Taiwan Area and Mainland Area and the '1992 Consensus'.[104] On 7 October 2008 Ma Ying-jeou was interviewed by a Japan-based magazine "World". He said that laws relating to international relations cannot be applied regarding the relations between Taiwan and the mainland, as they are parts of a state.[105][106][107]

President Tsai Ing-wen, in her first inauguration speech in 2016, acknowledged that the talks surrounding the 1992 Consensus took place without agreeing that a consensus was reached. She credited the talks with spurring 20 years of dialogue and exchange between the two sides. She hoped that exchanges would continue on the basis of these historical facts, as well as the existence of the Republic of China constitutional system and democratic will of the Taiwanese people.[108] In response, Beijing called Tsai's answer an "incomplete test paper" because Tsai did not agree to the content of the 1992 Consensus.[109] On June 25, 2016, Beijing suspended official cross-strait communications,[110] with any remaining cross-strait exchanges thereafter taking place through unofficial channels.[111]

In January 2019, Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party wrote an open letter to Taiwan proposing a one country, two systems formula for eventual unification. Tsai responded to Xi in a January 2019 speech by stating that Taiwan rejects "one country, two systems" and that because Beijing equates the 1992 Consensus with "one country, two systems", Taiwan rejects the 1992 Consensus as well.[112] Tsai rejected one country, two systems explicitly again in her second inauguration speech, and reaffirmed her previous stance that cross-strait exchanges be held on the basis of parity between the two sides. She affirmed the DPP position that Taiwan, also known as the Republic of China, was already an independent country, and that Beijing must accept this reality.[113] She further remarked that cross-strait relations had reached a "historical turning point."[114]

Inter-government[editar]

Semi-governmental contact is maintained through the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF) and the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS). Negotiations between the SEF and the ARATS resumed on 11 June 2008.[115]

Although formally privately constituted bodies, the SEF and the ARATS are both directly led by the Executive Government of each side: the SEF by the Mainland Affairs Council of the Executive Yuan of the ROC, and the ARATS by the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council of the PRC. The heads of the two bodies, Lin Join-sane and Chen Deming, are both full-time appointees and do not hold other government positions. However, both are senior members of their respective political parties (Kuomintang and Chinese Communist Party respectively), and both have previously served as senior members of their respective governments. Their deputies, who in practice are responsible for the substantive negotiations, are concurrently senior members of their respective governments. For the June 2008 negotiations, the main negotiators, who are deputy heads of the SEF and the ARATS respectively, are concurrently deputy heads of the Mainland Affairs Council and the Taiwan Affairs Office respectively.[cita requerida]

To date, the 'most official'[cita requerida] representative offices between the two sides are the PRC's Cross-Strait Tourism Exchange Association (CSTEA) in Taiwan, established on 7 May 2010, and ROC's Taiwan Strait Tourism Association (TSTA) in China, established on 4 May 2010. However, the duties of these offices are limited only to tourism-related affairs so far.

2008 meetings[editar]

First 2008 meeting[editar]

A series of meetings were held between the SEF and the ARATS at Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing from 11 June 2008 to 14 June 2008. By convention, SEF–ARATS negotiations proceed in three rounds: a technical round led by negotiators seconded from the relevant government departments, a draft round led by deputy heads of the two organisations, and a formal round led by the heads of the two organisations. In this case, however, both sides have already reached broad consensus on these issues on both the technical and political levels through previous negotiations via the non-governmental and inter-party channels. As a result, the initial technical round was dispensed with, and the negotiations began with the second, draft round.[115]

The two sides agreed to the following:

- Initiate direct passenger airline services every weekend from 4 July 2008. Both parties agreed to negotiate on the routes of cross-strait direct flights and establish direct communication procedures concerning air traffic management systems as soon as possible. But before the routes of direct flights are finalized, charter flights may temporarily fly across Hong Kong Flight Information Region. There is no need to stop in Hong Kong, but planes still have to fly through its airspace. Weekend charter flights shall fly from each Friday to the following Monday for a total of four full days.

- Opening Taiwan to Chinese tourists. Both parties agreed that Mainland Chinese tourists must travel to Taiwan in groups. Tourists must enter into, visit, and exit from Taiwan in groups. The maximum quota of tourists received by the party responsible for tourist reception shall not exceed the average of 3,000 persons per day, and each group shall consist of a minimum of ten persons and forty persons at the maximum, being in Taiwan for a maximum of ten days.[117]

- However, in 2012, it was agreed by both parties that individual tourists from the PRC cities of Beijing, Shanghai, and Xiamen were allowed to visit Taiwan. Later, tourists from Chengdu, Chongqing, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Guangzhou, and Tianjin were allowed to visit Taiwan individually. Finally, Fuzhou, Jinan, and Xi'an were to join the list by the end of 2012.[118] In 2019, the Chinese government stopped issuing permits for individual tourists to visit Taiwan, amid worsening cross-Strait relations.[119]

To facilitate the above, both sides also agreed to further discuss on the possibilities of exchanging representative offices, with an SEF office to be opened in Beijing and an ARATS office in Taipei to issue travel permits to cross-Strait visitors, among other duties.

Second 2008 meeting[editar]

Following an invitation issued by the SEF at the first meeting, the head of ARATS, Chen Yunlin, began a visit to Taiwan on 3 November 2008.[120] Items on the agenda raised by SEF Chairman Chiang Pin-kung included direct maritime shipping, chartered cargo flights, direct postal service, and co-operation in ensuring food safety, in response to the 2008 Chinese milk scandal,[120] while ARATS chairman Chen Yunlin raised the matters of direct freight service, and opening up air routes that directly cross the Taiwan Strait. Previous routes avoided crossing the Strait for security reasons, with planes detouring through Hong Kong or Japan air control areas.[121]

On 4 November 2008, ARATS and SEF signed a number of agreements in Taipei. The agreement relating to direct passenger flights increased the number of charter flights from 36 to 108 per week, operating daily instead of the four days a week previously. Flights would now operate to and from 21 Chinese cities. Flights would also take a more direct route. Private business jet flights would also be allowed. The agreement relating to cargo shipping allowed direct shipping between 11 sea ports in Taiwan and 63 in China. The shipping would be tax free. The agreement relating to cargo flights provided for up to 60 direct cargo flights per month. Finally, an agreement was made to set up food safety alerts between the two sides. [122]

During Chen's visit in Taipei, he was met with a series of strong protests directed at himself and Ma Ying-jeou, some of which were violent with Molotov cocktails being thrown by the protesters at riot police. A series of arrests were made after the protests.[123][124] Local police reported that 149 of its officers were injured during the opposition protests.[125] Consistent with the 1992 Consensus, Chen did not call Ma as "President".[126][127] Similarly, the representatives from Taiwan did not call the PRC President Hu Jintao as "President", but called him "General Secretary" in the previous meeting in Beijing.

China Post reported that some polls have indicated that the public may be pleased with Chen's visit, with about 50% of the Taiwanese public considered Chen's visit having a positive effect on Taiwan's development, while 18 to 26% of the respondents thought the effect would be negative.[128] In another poll, it suggested that 26% of the respondents were satisfied with the DPP Chairwoman Tsai Ing-wen's handling of the crowds in the series of protests, while 53% of the respondents were unsatisfied. The same poll also showed that 33% of the respondents were satisfied with President Ma's performance at his meeting with Chen Yunlin, while 32% of the respondents were not satisfied.[129]

Inter-party[editar]

The Kuomintang (former ruling party of Taiwan) and the Chinese Communist Party, maintain regular dialogue via the KMT–CCP Forum. This has been called a "second rail" in Taiwan, and helps to maintain political understanding and aims for political consensus between the two parties.

Inter-city[editar]

The Shanghai-Taipei City Forum is an annual forum between the city of Shanghai and Taipei. Launched in 2010 by then-Taipei Mayor Hau Lung-pin to promote city-to-city exchanges, it led Shanghai participation in the Taipei International Flora Exposition end of that year.[130] Both Taipei and Shanghai are the first two cities across the Taiwan Strait that carries out exchanges. In 2015, the newly elected Taipei Mayor Ko Wen-je attended the forum. He was addressed as Mayor Ko of Taipei by Shanghai Mayor Yang Xiong.[131]

Non-governmental[editar]

A third mode of contact is through private bodies accredited by the respective governments to negotiate on technical and operational aspects of issues between the two sides. Called the "Macau mode", this avenue of contact was maintained even through the years of the Chen Shui-bian administration. For example, on the issues of opening Taiwan to Chinese tourists, the accredited bodies were tourism industry representative bodies from both sides.[cita requerida]

Public opinion[editar]

According to an opinion poll released by the Mainland Affairs Council taken after the second 2008 meeting, 71.79% of the Taiwanese public supported continuing negotiations and solving issues between the two sides through the semi-official organisations, SEF and ARATS, 18.74% of the Taiwanese public did not support this, while 9.47% of the Taiwanese public did not have an opinion.[132]

In 2015, a poll conducted by the Taiwan Braintrust showed that about 90 percent of the population would identify themselves as Taiwanese rather than Chinese if they were to choose between the two. Also, 31.2 percent of respondents said they support independence for Taiwan, while 56.2 percent would prefer to maintain the status quo and 7.9 percent support unification with China.[133]

In 2016, a poll by the Taiwan Public Opinion Foundation showed that 51% approved and 40% disapproved of President Tsai Ing-wen's cross-strait policy. In 2017, a similar poll showed that 36% approved and 52% disapproved.[134] In 2018, 31% were satisfied while 59% were dissatisfied.[135]

Taiwanese polls have consistently showed rejection of the notion of "one China" and support for the fate of Taiwan to be decided solely by Taiwanese. A June 2017 poll found that 70% of Taiwanese reject the idea of "one China".[136] In November 2017, a poll by the Mainland Affairs Council showed that 85% of respondents believed that the Taiwan's future should be decided only by the people of Taiwan, while 74% wanted China to respect the sovereignty of the Republic of China (Taiwan).[137] In January 2019, a poll by the Mainland Affairs Council showed that 75% of Taiwanese rejected Beijing's view that the 1992 Consensus meant the "one China principle" under the framework of "one country, two systems". Further, 89% felt that the future of Taiwan should be decided by only the people of Taiwan.[138]

In 2020, an annual poll conducted by Academia Sinica showed that 73% of Taiwanese felt that China was "not a friend" of Taiwan, an increase of 15% from the previous year.[139] An annual poll run by National Chengchi University found that a record 67% of respondents identified as Taiwanese only, versus 27.5% who identified as both Chinese and Taiwanese and 2.4% who identified as Chinese only. The same poll showed that 52.3% of respondents favored postponing a decision or maintaining the status quo indefinitely, 35.1% of respondents favored eventual or immediate independence, and 5.8% favored eventual or immediate unification.[140]

On November 12, 2020, the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) poll was released and showed Taiwanese thinking on a set of topics. 90% of Taiwanese oppose China's military aggression against Taiwan. 80% believe maintaining cross-strait peace is the responsibility of both sides and not just Taiwan. 76% reject the "one country, two systems" approach proposed by Beijing. 86% believe only Taiwanese have right to choose the path of self determination for Taiwan.[141]

Sunflower Movement[editar]

In 2014, the Sunflower Student Movement broke out. Citizens occupied the Taiwanese legislature for 23 days, protesting against the government forcing through Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement. The protesters felt that the trade pact with China would leave Taiwan vulnerable to political pressure from Beijing.[142]

2016 meme campaign[editar]

In January 2016, the leader of the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party, Tsai Ing-wen, was elected to the presidency of the Republic of China.[143] On 20 January thousands of mainland Chinese internet users, primarily from the forum "Li Yi Tieba" (李毅貼吧), bypassed the Great Firewall of China to flood with messages and stickers the Facebook pages of the president-elect, Taiwanese news agencies Apple Daily and SET News, and other individuals to protest the idea of Taiwanese independence.[144][145][146]

Informal relations[editar]

The Three Links[editar]

Regular weekend direct, cross-strait charter flights between mainland China and Taiwan resumed on 4 July 2008 for the first time since 1950. Liu Shaoyong, China Southern Airlines chair, piloted the first flight from Guangzhou to Taipei. Simultaneously, a Taiwan-based China Airlines flight flew to Shanghai. As of 2015, 61 mainland Chinese cities are connected with eight airports in Taiwan. The flights operate every day, totaling 890 round-trip flights across the Taiwan Strait per week.[148] Previously, regular passengers (other than festive or emergency charters) had to make a time-consuming stopover at a third destination, usually Hong Kong.[149][150]

Taiwan residents cannot use the Republic of China passport to travel to mainland China and Mainland China residents cannot use the People's Republic of China passport to travel to Taiwan, as neither the ROC nor the PRC considers this international travel. The PRC government requires Taiwan residents to hold a Mainland Travel Permit for Taiwan Residents when entering mainland China, whereas the ROC government requires mainland Chinese residents to hold the Exit and Entry Permit for the Taiwan Area of the Republic of China to enter the Taiwan Area.

Economy[editar]

Since the resumption of trade between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait in 1979, cross-strait economic exchanges have become increasingly close. Predominantly, this involves Taiwan-based firms moving to, or collaborating in joint ventures, in Mainland China. The collective body of Taiwanese investors in Mainland China is now a significant economic force for both Mainland China and Taiwan. In 2014, trade values between the two sides reached US$198.31 billion, with imports from Taiwan to the mainland counted up to US$152 billion.[151]

In 2015, 58% of Taiwanese working outside Taiwan worked in Mainland China, with a total number of 420,000 people.[152]

Between 2001 and 2011, the percentage of Taiwanese exports to mainland China and Hong Kong grew from 27% to 40%.[153] In 2020, mainland China accounted for 24.3% of Taiwan's total trade and 20.1% of its imports, while Hong Kong accounted for 6.7% of its total trade volume.[154] Mainland Chinese exports to Taiwan account for 2% of total exports, and imports from Taiwan account for 7% of total imports.[155]

Since the governments on both sides of the strait do not recognize the other side's legitimacy, there is a lack of legal protection for cross-strait economic exchanges. The Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) was viewed as providing legal protection for investments.[156] In 2014 the Sunflower Student Movement effectively halted the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA).

Cultural, educational, religious and sporting exchanges[editar]

The National Palace Museum in Taipei and the Palace Museum in Beijing have collaborated on exhibitions. Scholars and academics frequently visit institutions on the other side. Books published on each side are regularly re-published in the other side, though restrictions on direct imports and the different writing systems between the two sides somewhat impede the exchange of books and ideas.[cita requerida]

Students of Taiwan origin receive special concessions in the National Higher Education Entrance Examination in mainland China.[cita requerida] There are regular programs for school students from each side to visit the other.[cita requerida] In 2019, there are 30,000 mainland Chinese and Hong Kong students studying in Taiwan.[157] There are also more than 7,000 Taiwanese students currently studying in Hong Kong.[158]

Religious exchange has become frequent. Frequent interactions occur between worshipers of Matsu, and also between Buddhists.[cita requerida]

The Chinese football team Changchun Yatai F.C. chose Taiwan as the first stop of their 2015 winter training session, which is the first Chinese professional football team's arrival in Taiwan, and they were supposed to have an exhibition against Tatung F.C., which, however, wasn't successfully held, under unknown circumstances.[cita requerida]

Humanitarian actions[editar]

Both sides have provided humanitarian aid to each other on several occasions.[cita requerida] Following the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, an expert search and rescue team was sent from Taiwan to help rescue survivors in Sichuan. Shipments of aid material were also provided under the co-ordination of the Red Cross Society of The Republic of China and charities such as Tzu Chi.[159]

Military build-up[editar]

Taiwan has more than 170,000 air raid shelters which would shelter much of the civilian population in the event of Chinese air or missile attack.[160]

Since 2016, the People's Republic of China has embarked on a massive military build-up.[161]

In addition, the United States has indicated that it would supply Taiwan's military with ships and planes, but has not provided significant numbers of either for some years[162][163] though Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said in 2011 that the United States would reduce arms sales to Taiwan if tensions are eased,[164] but that this was not a change in American policy.[165]

In 2012, PACCOM commander Willard said that there was a reduced possibility of a cross-strait conflict accompanying greater interaction, though there were no reductions in military spending on either side.[166]

In 2017, the United States began increasing military exchanges with Taiwan as well as passing two bills to allow high level visits between government officials.[167][168]

Under the Trump administration, more US military vessels have passed through the Strait than during President Barack Obama's term.[169]

In 2020 German Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer warned China not to pursue military action against Taiwan saying that such a decision would be a "major failure of statecraft” which would produce only losers.[170]

The Deputy Director-General of Taiwan's National Security Bureau Chen Wen-fan has stated that Xi Jinping intends to solve the Taiwan "Problem" by 2049.[171]

See also[editar]

Portal:China. Contenido relacionado con Taiwan.

Portal:China. Contenido relacionado con Taiwan.- Chen-Chiang summit

- Cross-Straits Economic Trade and Culture Forum

- Cross-Strait Peace Forum

- Foreign relations of China

- Foreign relations of Taiwan

- North Korea–South Korea relations

- China–United States relations

- Taiwan–United States relations

- Political status of Taiwan

- Wang-Koo summit

- Zhu Rongji

References[editar]

- ↑ Gold, Thomas B. (March 1987). «The Status Quo is Not Static: Mainland-Taiwan Relations». Asian Survey 27 (3): 300-315. JSTOR 2644806. doi:10.2307/2644806.

- ↑ Blanchard, Ben; Lee, Yimou (3 January 2020). «Factbox: Key facts on Taiwan-China relations ahead of Taiwan elections». Reuters. Consultado el 7 June 2020.

- ↑ Green, Leslie C. The Contemporary Law of Armed Conflict. p. 79.

- ↑ Lee, I-chia (12 March 2020). «Virus Outbreak: Flights bring 361 Taiwanese home». Taipei Times. Consultado el 7 June 2020.

- ↑ «Demographic Yearbook—Table 3: Population by sex, rate of population increase, surface area and density». UN Statistics. 2007. Archivado desde el original el 24 December 2010. Consultado el 31 July 2010. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «China». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archivado desde el original el 13 November 2012. Consultado el 16 November 2012. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ a b «Number of Villages, Neighborhoods, Households and Resident Population». MOI Statistical Information Service. Archivado desde el original el 29 March 2014. Consultado el 2 February 2014. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «President lauds efforts in transitional justice for indigenous people». Focus Taiwan. Archivado desde el original el 21 July 2017. Consultado el 19 July 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Hakka made an official language». Taipei Times. Archivado desde el original el 30 December 2017. Consultado el 29 December 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Official documents issued in Aboriginal languages». Taipei Times. 20 July 2017. Archivado desde el original el 20 July 2017. Consultado el 20 July 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ a b c «GDP (current US$) World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files.». World Bank. 2 August 2019. Archivado desde el original el 6 September 2019. Consultado el 2 August 2019. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ a b c d «Republic of China (Taiwan)». International Monetary Fund. Archivado desde el original el 29 de marzo de 2014. Consultado el 28 de octubre de 2013. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ a b «About China». UNDP in China. Archivado desde el original el 19 de enero de 2015. Consultado el 17 de enero de 2015. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «China's Economy Realized a Moderate but Stable and Sound Growth in 2015». National Bureau of Statistics of China. 19 January 2016. Archivado desde el original el 21 January 2016. Consultado el 20 January 2016. «Taking the per capita disposable income of nationwide households by income quintiles, that of the low-income group reached 5,221 yuan, the lower-middle-income group 11,894 yuan, the middle-income group 19,320 yuan, the upper-middle-income group 29,438 yuan, and the high-income group 54,544 yuan. The Gini Coefficient for national income in 2015 was 0.462.» Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Table 4. Percentage Share of Disposable Income by Quintile Group of Households and Income Inequality Indices». Report on The Survey of Family Income and Expenditure. Taipei, Taiwan: Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics. 2010. Archivado desde el original el 12 de mayo de 2012. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Data set». dgbas.gov.tw. Archivado desde el original el 17 de marzo de 2012. Consultado el 3 de enero de 2014. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «China trade now bigger than US». The Daily Telegraph. 10 February 2013. Archivado desde el original el 14 February 2013. Consultado el 15 February 2013. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Taiwan Timeline – Retreat to Taiwan». BBC News. 2000. Archivado desde el original el 24 de junio de 2009. Consultado el 21 de junio de 2009. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ a b «Trends in world military expenditure, 2019». Sipri.

- ↑ Zhang, Qiyun. (1959) An outline history of Taiwan. Taipei: China Culture Publishing Foundation

- ↑ Sanchze-Mazas (ed.) (2008) Past human migrations in East Asia : matching archaeology, linguistics and genetics. New York: Routledge.

- ↑ Brown, Melissa J. (2004) Is Taiwan Chinese? : the impact of culture, power, and migration on changing identities. Berkeley: University of California Press

- ↑ Lian, Heng (1920). [The General History of Taiwan]

|título-trad=requiere|título=(ayuda) (en chino). OCLC 123362609. Parámetro desconocido|script-title=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Morris, 2002, pp. 4–18.

- ↑ «Archived copy». Archivado desde el original el 28 de febrero de 2017. Consultado el 24 de febrero de 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Qi, Bangyuan. Wang, Dewei. Wang, David Der-wei. [2003] (2003). The Last of the Whampoa Breed: Stories of the Chinese Diaspora. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13002-3. pg 2

- ↑ MacFarquhar, Roderick. Fairbank, John K. Twitchett, Denis C. [1991] (1991). The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24337-8. pg 820.

- ↑ a b c d e Tsang, Steve Yui-Sang Tsang. The Cold War's Odd Couple: The Unintended Partnership Between the Republic of China and the UK, 1950–1958. [2006] (2006). I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-842-0. p 155, p 115-120, p 139-145

- ↑ Bush, Richard C. [2005] (2005). Untying the Knot: Making Peace in the Taiwan Strait. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-1288-X.

- ↑ Lin, Syaru Shirley (June 29, 2016). Taiwan's China Dilemma. Stanford University Press. pp. 96-98. ISBN 978-0804799287.

- ↑ Cheng, Allen T. «Did He Say 'One China'?». Asiaweek. Consultado el 11 March 2021.

- ↑ «Taiwan – timeline». BBC News. 9 March 2011. Archivado desde el original el 9 December 2011. Consultado el 6 de enero de 2012. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Wang, Vincient Wei-cheng (2002). «The Chen Shui-Bian Administrations MainlandPolicy: Toward a Modus Vivendi or ContinuedStalemate?». Politics Faculty Publications and Presentations: 115.

- ↑ «Mainland scrambles to help Taiwan airlines». Archivado desde el original el 4 March 2016. Consultado el 3 April 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Sisci, Francesco (5 April 2005). «Strange cross-Taiwan Strait bedfellows». Asia Times. Archivado desde el original el 12 de mayo de 2008. Consultado el 15 de mayo de 2008. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Zhong, Wu (29 March 2005). «KMT makes China return in historic trip to ease tensions». The Standard. Archivado desde el original el 2 June 2008. Consultado el 16 de mayo de 2008. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Decisive victory for Ma Ying-jeou». Taipei Times. 23 March 2008. Archivado desde el original el 3 December 2013. Consultado el 10 April 2013. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Chinese, U.S. presidents hold telephone talks on Taiwan, Tibet». Xinhuanet. 27 March 2008. Archivado desde el original el 12 de mayo de 2008. Consultado el 15 de mayo de 2008. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ [Hu Jintao meets Vincent Siew; they exchanged opinions on cross-Strait economic exchange and co-operation]

|título-trad=requiere|título=(ayuda) (en chino). Xinhua News Agency. 12 April 2008. Archivado desde el original el 21 April 2008. Consultado el 2 de junio de 2008. Parámetro desconocido|url-status=ignorado (ayuda); Parámetro desconocido|script-title=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «晤諾貝爾得主 馬再拋兩岸互不否認 (Meeting Nobel laureates, Ma again speaks of mutual non-denial)». Liberty Times (en chino). 19 April 2008. Archivado desde el original el 25 de mayo de 2008. Consultado el 2 de junio de 2008. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ (en chino). Xinhua News Agency. 13 June 2008 https://web.archive.org/web/20090213204559/http://news.xinhuanet.com/tw/2008-06/13/content_8360544.htm. Archivado desde el original el 13 February 2009. Consultado el 15 de junio de 2008. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda); Parámetro desconocido|script-title=ignorado (ayuda); Falta el|título=(ayuda) - ↑ (en chino). Xinhua News Agency. 13 June 2008 https://web.archive.org/web/20090213204603/http://news.xinhuanet.com/tw/2008-06/13/content_8360914.htm. Archivado desde el original el 13 February 2009. Consultado el 15 de junio de 2008. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda); Parámetro desconocido|script-title=ignorado (ayuda); Falta el|título=(ayuda) - ↑ a b c d e «Taiwan opens up to mainland Chinese investors». The Times (London). 1 de mayo de 2009. Archivado desde el original el 8 de mayo de 2009. Consultado el 4 de mayo de 2009. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ John Pike. «President Ma urges China to dismantle missiles targeting Taiwan». globalsecurity.org. Archivado desde el original el 23 de junio de 2011. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «China: US spat over Taiwan could hit co-operation». Agence France-Presse. 2 February 2010. Archivado desde el original el 6 February 2010. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Kelven Huang and Maubo Chang, ROC Central News Agency China military budget rises sharply: defense ministry (enlace roto disponible en este archivo).

- ↑ Ho, Stephanie. "China Urges Unification at 100th Anniversary of Demise of Last Dynasty." (enlace roto disponible en este archivo). VoA, 10 October 2011.

- ↑ «China unveils 31 measures to promote exchanges with Taiwan». focustaiwan.tw. Archivado desde el original el 3 de diciembre de 2013. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Taiwan, Chinese ministers meet in groundbreaking first». focustaiwan.tw. Archivado desde el original el 24 de diciembre de 2013. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Video en YouTube.

- ↑ «MAC, TAO ministers to meet today». Archivado desde el original el 22 de febrero de 2014. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «MAC Minister Wang in historic meeting». Taipei Times. Archivado desde el original el 3 de marzo de 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «China and Taiwan Hold First Direct Talks Since '49». The New York Times. 12 February 2014. Archivado desde el original el 4 April 2016. Consultado el 3 April 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «China-Taiwan talks pave way for leaders to meet». The Sydney Morning Herald. Archivado desde el original el 9 de mayo de 2014. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «MAC Minister Wang in historic meeting». Taipei Times. Archivado desde el original el 22 de febrero de 2014. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ [Taiwan Affairs Office chairman Zhang Zhijun and Taiwan's Mainland Affairs Council "responsible official" Wang Yu-chi hold an official meeting: pictures and video]

|título-trad=requiere|título=(ayuda). Xinhua News Agency. Archivado desde el original el 2 de marzo de 2014. Parámetro desconocido|script-title=ignorado (ayuda); Parámetro desconocido|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Cross-Strait affairs chiefs hold first formal meeting – Xinhua – English.news.cn». Xinhua News Agency. Archivado desde el original el 2 de marzo de 2014. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Chou Chih-chieh (15 October 2014), Beijing seems to have cast off the 1992 Consensus (enlace roto disponible en este archivo). China Times

- ↑ «Hotline established for cross-strait affairs chiefs». Archivado desde el original el 4 de marzo de 2016. Consultado el 14 de enero de 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «China picks up hotline call». 6 February 2016. Archivado desde el original el 9 April 2016. Consultado el 3 April 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Minister of justice heads to China on historic visit». 29 March 2016. Archivado desde el original el 7 April 2016. Consultado el 3 April 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Tai, Ya-chen; Chen, Chun-hua; Huang, Frances (17 January 2016). «Turnout in presidential race lowest in history». Central News Agency. Archivado desde el original el 19 January 2016. Consultado el 17 January 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Diplomat, Yeni Wong, Ho-I Wu, and Kent Wang, The. «Tsai's Refusal to Affirm the 1992 Consensus Spells Trouble for Taiwan». The Diplomat. Archivado desde el original el 4 de octubre de 2017. Consultado el 4 de octubre de 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Former president Ma to visit Hong Kong - Focus Taiwan». Archivado desde el original el 4 de junio de 2016. Consultado el 7 de agosto de 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Ramzy, Austin (14 June 2016). «Taiwan Bars Ex-President From Visiting Hong Kong». New York Times. Archivado desde el original el 23 June 2016. Consultado el 7 August 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Full text of former President Ma Ying-jeou's video speech at SOPA». Central News Agency. Archivado desde el original el 24 July 2016. Consultado el 7 August 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Local gov't officials hold meeting with Beijing». Archivado desde el original el 23 de septiembre de 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Local government heads arrive in Beijing for talks – Taipei Times». 18 September 2016. Archivado desde el original el 19 de septiembre de 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Kuomintang News Network». Archivado desde el original el 24 de septiembre de 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Archived copy». Archivado desde el original el 24 de noviembre de 2016. Consultado el 24 de noviembre de 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Funeral for uncle of China's first lady held in Chiayi; KMT officials attend - Taipei Times». 24 November 2016. Archivado desde el original el 24 de noviembre de 2016. Consultado el 24 de noviembre de 2016. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «President Tsai calls for new model for cross-strait ties | ChinaPost». ChinaPost. 3 October 2017. Archivado desde el original el 4 October 2017. Consultado el 4 de octubre de 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Tsai renews call for new model on cross-strait ties – Taipei Times». taipeitimes.com. 4 October 2017. Archivado desde el original el 3 October 2017. Consultado el 4 de octubre de 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Relations with Beijing bedevil Taiwan's Tsai one year on». Nikkei Asia Review. Archivado desde el original el 19 de mayo de 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ a b hermesauto (18 de octubre de 2017). «19th Party Congress: Any attempt to separate Taiwan from China will be thwarted». The Straits Times. Archivado desde el original el 18 de octubre de 2017. Consultado el 19 de octubre de 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Archived copy». news.ifeng.com. Archivado desde el original el 19 de octubre de 2017. Consultado el 19 de octubre de 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|script-title=ignorado (ayuda); Parámetro desconocido|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Archived copy». Archivado desde el original el 19 de octubre de 2017. Consultado el 19 de octubre de 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|script-title=ignorado (ayuda); Parámetro desconocido|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Archived copy». Archivado desde el original el 19 de octubre de 2017. Consultado el 19 de octubre de 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|script-title=ignorado (ayuda); Parámetro desconocido|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ News, Taiwan. «China bans tour groups to Vatican, Palau to isolate Taiwan – Taiwan News». Archivado desde el original el 27 de noviembre de 2017. Consultado el 18 de diciembre de 2017. Parámetro desconocido

|url-status=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Ihara, Kensaku (9 April 2018). «Pro-independence forces in Taiwan align to push referendum». Nikkei Asian Review (Japan). Archivado desde el original el 6 de mayo de 2018. Consultado el 16 de mayo de 2018. Parámetro desconocido